The knee is the largest and strongest joint in the body, consisting of the distal femur, the proximal end of the tibia, and the patella. The ends of these three bones are covered with cartilage that protects and cushions them as the knee bends and straightens. There are two wedge-shaped pieces of fibrocartilage- the lateral meniscus and the medial meniscus – that act as shock absorbers between the femur and tibia. They are tough and rubbery to help cushion and stabilize the joint, and are surrounded by a synovial membrane that lubricates the cartilage and reduces friction. There are also the cruciate and collateral ligaments, and the joint is crossed by several tendons.

Although exact numbers are difficult to determine, mechanical knee pain accounts for a significant portion of exercise- and running-related injuries. Knee pain is a complex subject and leading researchers advance more than one theory of etiology. This article provides an overview of the topic and presents some treatment options that can be used as a starting point for further investigation.

Biomechanics of Knee Pain

It has been proposed that mechanically induced knee pain has its origin in the biomechanics of the lower limb. In normal gait, heel strike occurs with the foot in an inverted position. As loading response proceeds, the plantar foot everts rapidly. The resulting pronation of the subtalar joint (STJ) initiates an eversion of the calcaneus and a lowering of the medial longitudinal arch. This, in turn, allows internal rotation of the tibia. Above the tibia, the femur also rotates and there is a transverse plane internal rotation of the knee. If pronation is excessive, lower-limb compensations include knee abduction or hip adduction. The harmonic sequence of STJ pronation (frontal plane) correlating to internal tibial rotation (transverse plane) is necessary for shock absorption, but it can affect the knee, increasing patellofemoral (PF) joint contact and creating stress locally.

It is thought, though not universally accepted, that the torque from knee rotation and abduction may be the cause of pain. When a patient demonstrates foot pronation late in the gait cycle, failing to resupinate appropriately, the resulting knee valgus strains the tendons and ligaments, potentially altering patella alignment. Foot orthotics and physical therapy can address some of these characteristics by properly supporting the foot, adjusting the timing and duration of pronation, and strengthening the muscle groups involved. Not all patients will respond to these interventions but it is possible to quickly test their potential benefit. You can often determine if the pain is mechanical in origin by using some combination of in-office prefabricated foot orthotics, taping, or sole wedges.

There is good evidence supporting the use of custom foot orthotics, and three papers highlighting their efficacy were cited in an article in the September 2016 issue of The O&P EDGE (www.oandp.com/articles/2016-09_08.asp). When designing foot orthotics for knee pain, the device should fully support the medial column of the foot, helping reduce pronation and knee valgus, thereby limiting the force moments at the knee. Usually a full-width, semi-rigid, thermoplastic orthotic works best. A deep heel cup and a zero degree, flat extrinsic post provides good stability, which restricts calcaneal eversion and avoids end range of motion (ROM). Interestingly, the provision of foot orthotics does not necessarily translate to visibly better biomechanics at the knee. Some studies have noted the benefit of foot orthotics without observing measurable changes in kinematics. It seems part of their effect may be in altering the loading rate and timing of forces along the closed kinetic chain rather than simply aligning the leg and reducing knee valgus.

THE NAME GAME

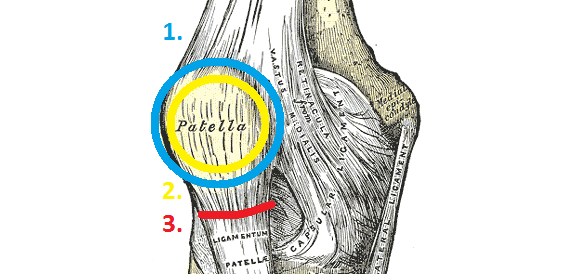

OSGOOD-SCHLATTER DISEASE is a common cause of knee pain in growing adolescents. It is an inflammation of the area just below the knee where the patella tendon attaches to the tibia. Osgood-Schlatter disease most often occurs during growth spurts. Children who participate in athletics- especially running and jumping sports-are at an increased risk and may experience pain, tenderness, or swelling at the tibial tubercule.

SINDING-LARSEN-JOHANSSON DISEASE is another cause of anterior knee pain, again usually seen in adolescents around the time of a growth spurt. It presents as activity-related anterior knee pain and there is typically tenderness over the inferior pole of the patella. The mechanism is thought to be persistent, repetitive traction by the patella tendon, possibly due to tight quadriceps muscles or a sudden relative lengthening of the femur. It may be considered similar to Osgood- Schlatter disease except it occurs more superior, at the distal end of the patella instead of at the tibial tubercule. For both conditions, therapies of rest, stretching and strengthening, and sometimes the use of anti-inflammatory medications, can prove beneficial. Foot orthotics help in certain cases, especially if excessive foot pronation is thought to be contributing torsional force at the knee.

CHONDROMALACIA PATELLA, sometimes referred to as runner’s knee, is an inflammation or chronic irritation of the posterior surface of the patella. The distinguishing characteristic of chondromalacia is softening of the cartilage, and patients sometimes also report a grinding sensation. The patella cartilage acts as a natural shock absorber, and once erosion occurs and the surface is no longer smooth, movement can become painful. It may occur due to an acute injury or overuse from participating in high-activity sports. Pain often feels worse after prolonged sitting. Rest may help. But if the root cause is patella malalignment or muscle imbalance, it may be necessary to seek physical therapy or arthroscopic surgery.

PATELLOFEMORAL PAIN SYNDROME (PFPS) is defined as diffuse pain around or behind the patella, which is aggravated by activities that load the PF joint, such as squatting, running, jumping, and ascending and descending stairs. The term is used rather broadly but should be kept distinct from tendinopathies and ligament insufficiencies. It differs from chondromalacia in that there is no cartilage damage. Symptoms include crepitus, tenderness on palpation of the patella edges, and pain upon straightening the knee following sitting. Currently, the best available test is to check for anterior knee pain elicited during a squat.

PES ANSERINE BURSITIS is medial knee pain resulting from inflammation of the bursa located between the tibia and three tendons of the hamstring muscles. Pain usually increases with exercise and is felt about two to three inches below the medial knee. It can be the result of overuse, sudden exertion, tight hamstrings, obesity, or other factors that put stress on the knee. As with any bursitis, conservative measures, such as rest and icing, often help. In addition, foot orthotics that limit pronation have been shown as beneficial.

KNEE OSTEOARTHRITIS is a distinct degenerative joint disease characterized by stiffness and pain and should be considered separate from anterior knee pain. Likewise, any structural knee damage or ligamentous injuries should be differentiated from those that are mechanical in origin.

Research

Intuitively, the notion of lower-limb rotation and knee abduction provides a framework to consider the cause of knee pain. However, numerous studies examining knee kinetics and kinematics indicate there are other subtle factors that weigh into the equation. For example, not all people with flat feet experience knee pain, and simply raising the medial arch does not predictably eliminate the problem. In recent years, an academic forum has been organized to gather and discuss the best available research. They have met biennially since 2009 to develop consensus statements on terminology, etiology, and treatments. For a more in-depth look at their work and a host of further references, search “International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat” on PubMed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/pubmed.

One emerging idea is there may be subgroups within patient cohorts who respond differently to treatments. For example, women are far more likely to experience PFPS than men, and teenage girls are at more than twice the risk compared to boys. This suggests the causes may be different for men and women and that perhaps the treatment plans should also be different. At the proximal end of the leg, other researchers have noted a link between hip mechanics and PFPS. In some studies, hip strength and ROM (abduction and extension) have been correlated to PFPS. The underlying cause of knee pain is an area rich in opportunity for investigation, and much work needs to be done to develop a comprehensive theory and patient-specific treatment protocols.

Séamus Kennedy, BEng (Mech), CPed, is president and co-owner of Hersco Ortho Labs, New York. He can be contacted via e-mail at seamus@hersco.com or by visiting www.hersco.com.