Few names in the world of podiatry and biomechanics are as well known as Justin Wernick, DPM. His career as a practitioner, innovator, lab owner, and international academic lecturer spans more than five decades.

Early Loss Leads to Determination

Wernick was born in 1936 in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. His early childhood was marked by loss. His mother died when he was three years old. He then went to live with his grandparents, who also both died when he was young – his grandfather when Wernick was six years old and his grandmother two years later. After that, he was raised by an aunt. He speaks of the lesson that he learned from these early losses with his characteristic pragmatism. “It made me realize that there was no one there for me,” Wernick says. “I would have to take care of myself.”

Wernick says he was “an average student, set to graduate with poor marks” and limited prospects. However, he remembers being impressed by the local chiropodist, who seemed to be “well organized and successful.” That physician gave him information about the pathway to podiatry school. Wernick says he discovered that if he could earn credits in biology, physics, and chemistry at Long Island University (LIU), Brooklyn campus, he would be able to transfer to the LIU College of Podiatry, Harlem, New York (now the New York College of Podiatric Medicine (NYCPM)), which was under the administration of LIU, Brooklyn, at the time. No one in his family had gone to college, and despite the fact that there were no funds readily available, he began his college education with the clear goal of pursuing a career in podiatry. He enjoyed his three years at LIU and did well in his undergraduate studies, particularly in biology. During the school year, he worked the 6-10 p.m. shift at the post office to pay the $12 per credit tuition, and during the summers he worked in the Catskills’ resorts as a waiter.

After his third year of podiatric study, Wernick says he realized that he wanted to be a surgeon, so he applied to the pioneering podiatric surgical residency program at Civic Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, directed by Earl Kaplan, DPM. It was the only program of its kind in the country at that time, and there were only two residency slots available, neither of which was offered to Wernick. He says he was crestfallen when he learned that he had not been accepted. Despite the setback, his hard work and dedication paid off when he graduated in 1959 with a doctor of podiatry (PodD) degree from M.J. Lewi College of Podiatry – the former LIU College of Podiatry, which had been renamed after the affiliation with LIU ended in 1957.

Launching a Podiatric Career

Having completed his studies, Wernick was required to complete mandatory national service, so he joined the Army Reserves at Fort Dix, New Jersey. In April 1960, he commenced his professional career covering a very busy chiropody practice in Midtown Manhattan, New York. He and his wife were living with his mother-in-law when he found a built-out office for rent in Seaford, Long Island, New York.

He opened his practice in January 1961, willing to tend to any foot complaint for $5 a visit. In that first year, he grossed a meager $3,000, which left little for salary. Around that time, Gouverneur Hospital, Manhattan, was opening a new podiatry clinic. Wernick began working there part time to supplement his income. He and his wife were living in a rental studio when their daughter was born in 1963. Eventually they bought a house in Massapequa, Long Island, which was set up with a private physician’s office. He was now working at three practices and beginning to do well financially.

New Theories Lead to Innovative Foot Orthotics

A major turning point in Wernick’s views of podiatric practice came in 1963 when he first heard Merton Root, DPM, speak at a podiatry conference. Root, a podiatrist from San Francisco, California, was part of a physicians group that was developing new theories regarding foot function and pathology. Prior to this, little was understood about foot function and the internal joint relationships. Rather, feet were examined statically and characterized and treated based on descriptions of outward appearance, such as fleshy, high arched, or flat.

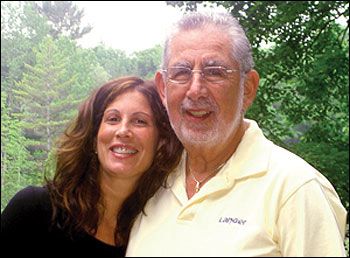

Wernick with his daughter, Elissa Wernick, who is a podiatrist as well. Photographs courtesy of Justin Wernick.

Wernick intuitively realized this new science, although complex, was worth understanding. After that meeting, a group of podiatrists invited Root back to New York so they could learn more. They had to pay his airfare and expenses, but he agreed. They flew him out about every three months, persistently asking him questions, tape recording his sessions, and then debating the answers among themselves. Wernick says, “We realized there was a cohesiveness and science to the orthopedics, more than had been taught up to this [point]. It included a basis for measurement, and it was also predictive.”

As the New York group’s understanding developed, they began to experiment making the new style of functional foot orthotics from an acrylic material called Rohadur. Wernick and his colleagues began taking patients’ plaster casts non-weight bearing with a neutral reference position. Gait, which had previously been ignored, also became part of their treatment equation. They started to see results. However, there were no labs making these devices, so they had to fabricate the orthotics themselves.

Soon Wernick was being invited to share his knowledge, and he started to lecture informally to podiatry groups. He also began working closely with Sheldon Langer, DPM, whom he had met in the study group that he was running, and they covered for each other at their respective private practices.

Wernick says that in 1968 he and Langer decided it would be beneficial to teach someone else how to manufacture the new type of orthotics. Because Wernick was lecturing nationally, and they wanted to avoid any appearance of impropriety, they named the business Langer Acrylic Lab. In 1969, each invested $5,000 to build and outfit a small garage behind Langer’s house, where they worked at night. The business plan was simple, Wernick says: “Train one technician, get a few podiatrists to send us their work, and that way we could pay [the technician] and have our own devices made.” From this humble beginning, Langer Biomechanics was launched.

Academia and Growing Business Ventures

Wernick’s academic career continued to grow as he became a member of the faculty at his alma mater in 1969 and began to teach biomechanics. Together, Wernick and Langer attended conventions, demonstrated casting techniques, and slowly converted the profession. There was a clear market for functional orthotics. In the early ’70s, they moved to a larger facility and hired more skilled technicians to run the lab. This freed them to travel and educate new customers. They began the Langer Newsletter, a technical bulletin that furthered the science and understanding of biomechanics. They continued to expand the business and sought newer materials to work with. Through testing, they eventually developed and trademarked the polyethylene Sporthotic®. They also introduced the material Professional Protective Technology (PPT) from Rogers, headquartered in Rogers, Connecticut, to the profession, and became the exclusive distributor.

The arrival of the American running boom in the mid-70s coincided perfectly with the advances in the understanding of biomechanics and orthotics in the podiatric sphere. There was an explosion in demand for sports medicine, and podiatry and orthotics were seen as critical components in keeping runners injury free. They started receiving calls from all over the country seeking referrals for a sports podiatrist, which led Wernick and Langer to become involved in the early development of the American Academy of Podiatric Sports Medicine. They also frequently ran weekend seminars with top faculty that attracted more than 400 attendees.

Langer Acrylic Lab continued to grow, eventually expanding nationally with locations in California and one in Chicago, Illinois, as well as a larger facility in Deer Park, New York. With the backing of an investor from the United Kingdom, they opened a facility in England in 1980, and also added sales offices in Japan and Israel. While the company was successful, its rapid growth came with challenges in the form of competition from offshoot labs and debt used to fuel growth.

Wernick and Langer continued pursuing new technology in the orthotic and podiatric industry with the development of the Electrodynogram (EDG), an in-office gait-analysis instrument that used seven plantar foot sensors, and the Langer TRAFO, a tone-reducing AFO for children with cerebral palsy. There was also a plan to open TRAFO clinics across the country, but expansion required additional funds in the form of outside investors. This drove the decision to first cede 10 percent of the company to a venture capitalist and then to take the company public in 1984. At that point, the company had grown from a small backyard venture, and Wernick had persevered from a student working part-time jobs to pay tuition to a businessman with a 20 percent interest in a company valued at more than $17 million.

The 1980s saw changes in the business climate for orthotics as physical therapists and chiropractors entered the arena and competition from smaller labs intensified, driving down profit margins. The financial constraints of the situation caused them to close down the Chicago location, and Wernick says it led to additional tensions between the partners, ultimately resulting in Langer leaving the company. Wernick describes this as “the most stressful period of my life.”

By the 2000’s, Wernick had scaled back his involvement in the day-to-day operations of the lab. He had remained active with lecturing throughout his business ventures and podiatry practice, as well as maintaining faculty status at NYCPM, eventually becoming the chairman of the department of orthopedics. He also joined the staff of Eneslow Pedorthic Institute, New York, New York, as the medical director, where he had taught classes beginning in 1999. He officially retired from academia in 2012 after 44 years of providing education.

Wernick’s Wisdom

While he no longer actively practices, Wernick says he passionately believes in the value and significance of foot care. “By caring for feet you can genuinely change people’s lives. Foot health directly affects quality of life.” For those interested in providing foot care, his advice is simple, “Find an area of expertise, develop yourself, and market it. There are well over 300 million Americans…600 million feet! There is plenty of potential and opportunity to find a niche. But you must be able to demonstrate your value.”

Wernick’s long career and his dedication to his profession demonstrate the lesson he says he learned in childhood, “No one is going to do it for you.”

Séamus Kennedy, BEng (Mech), CPed, is president and co-owner of Hersco Ortho Labs, New York. He can be contacted via e-mail at seamus@hersco.com or by visiting www.hersco.com.