Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome (TTS) is an entrapment neuropathy due to compression of the tibial nerve or one of its branches. Despite being recognized much earlier, it was first labelled as a distinct pathology of the foot in the early 1960’s and described as “pain in the proximal medial arch and paresthesia along the lateral and medial plantar nerves”. Paresthesia is the pins-and-needles prickling sensation that occurs due to nerve restriction. Although relatively rare, it is a painful and debilitating condition of the foot that results from compression of the posterior tibial nerve. Researchers suspect it is likely under-diagnosed as the symptoms mimic several other foot maladies.

Anatomy

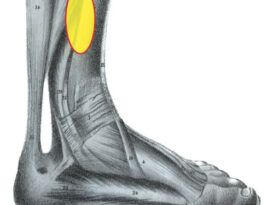

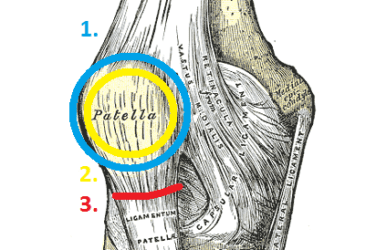

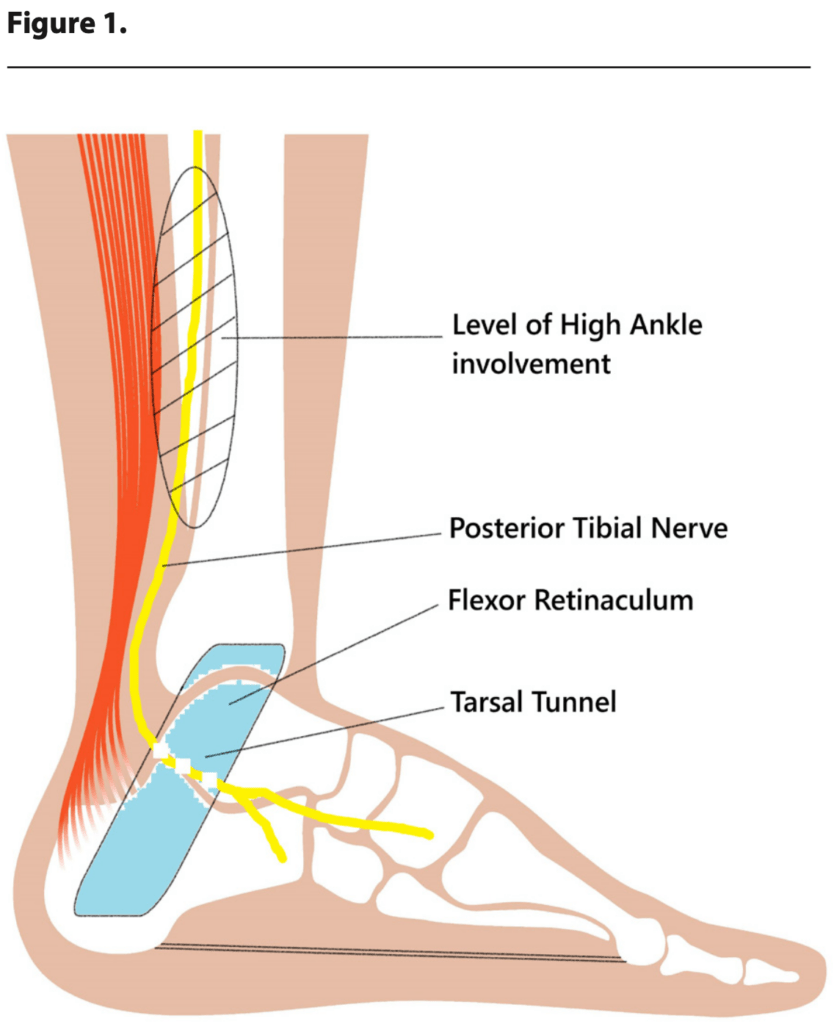

The tibial nerve enters into the foot behind the medial malleolus and under the fibrous flexor retinaculum. The flexor retinaculum, also known as the laciniate ligament, is a dense band of fascia that runs from the medial malleolus to the calcaneus covering and protecting several flexor tendons, blood vessels and nerves (Figure 1). The tarsal tunnel is the narrow conduit between the flexor retinaculum and the medial talus-calcaneus. It guides and protects the Tibialis posterior, the flexor Digitorum longus, the posterior tibial Artery and Vein, the tibial Nerve and the flexor Hallucis longus. These can be recalled by the mnemonic “Tom, Dick and very nervous Harry”.

The inferior aspect of the flexor retinaculum blends with the plantar fascia and both are anchored at the calcaneus. It has been proposed that tension on the plantar fascia – due to pronation – stretches the flexor retinaculum, decreasing the channel size and restricting the tibial nerve. Thus, a pronating foot with a valgus heel may aggravate the condition.

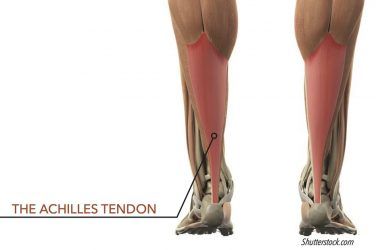

More recent investigations reveal TTS symptoms may also result from high tibial nerve entrapment – an impingement superior and proximal to the tunnel itself (Figure 1). Compression or restriction of the tibial nerve at the level of the high ankle is now being implicated in more than half of the cases.1 Nerve compression 10 – 16cm above the laciniate ligament can cause the same shooting pain down into the foot. It is believed the nerve gets entrapped in the fascia of the lower fibers of the gastrocnemius muscle – at the calf muscle belly transition.

Risk Factors

TTS occurs when there is traction or compression on the tibial nerve leading to numbness, weakness and/or a burning-type pain that usually extends distally from the medial ankle and heel into the plantar foot and sometimes to the toes. It presents more commonly in females and athletes and is associated with moderate to severe pes planus indicating a biomechanical component for both the etiology and the treatment. Currently many instances are deemed idiopathic but certain cases are attributable to traumatic injury, repetitive sports overuse or post-op complications.

Anything that takes up space in the tunnel can increase pressure on the nerve, so TTS may also arise from swelling in the surrounding tissues or vessels. This includes blockages or obstructions such as lesions, tumors, ganglions, varicosities or edema. Systemic inflammation from conditions such as Rheumatoid Arthritis, Diabetes Mellitus or even high BMI can also pressure the nerve.

Biomechanics and Orthotics

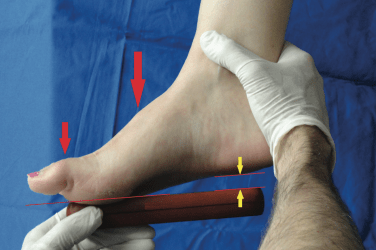

If the condition is due to foot eversion, causing traction on the nerve, it can often be confirmed with a quick and simple clinical test. With the patient seated hold the foot in maximal dorsiflexion and eversion for 10-15 seconds with the metatarsal phalangeal joints dorsiflexed. This creates non-weight bearing subtalar joint (STJ) pronation and tenses the flexor retinaculum. If local tenderness occurs or there is tingling on the plantar aspect of the foot there is a strong likelihood of TTS. The corollary of this test indicates that maintaining the foot in a less everted, more neutral position will alleviate symptoms.

In addition, cadaver studies have determined that there is an increase of pressure in the TT compartment when the foot is pronated as compared to the neutral position. It was also noted that there was less pressure in the channel when the foot was slightly plantarflexed and inverted.2

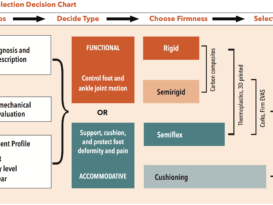

Custom foot orthotics are an excellent way to control rearfoot motion and maintain the calcaneus in a more vertical position. Typical prescriptions for TTS include a deep heel cup (>18mm) and some degree of extrinsic rearfoot posting. The orthotic material should be semi-rigid, providing stability, and the cast modifications may include a medial heel skive to increase the ground reaction force under the hindfoot. If the patient will tolerate it, a medial flange will further support the longitudinal arch. Finally, a heel lift of 3–6mm will slightly plantarflex the foot reducing pressure in the tarsal tunnel.

The effectiveness of orthotics always depends on the footwear that will be worn. First, ensure the patient wears well-fitting shoes with removable inlays that accommodate the device. Second, the shoe itself can provide a component of support. Strong high counters and firm outsoles will buttress the orthotic and resist the tendency of the foot to collapse. To counteract severe eversion external shoe modifications such as a medial flare may also provide some benefit.

In more advanced cases, when the syndrome is of a mechanical origin, a plastic-in-leather ankle gauntlet, AFO or other brace may be prescribed. Each of these devices further restricts STJ and rearfoot motion alleviating the pain, but as always shoe fit will be a concern.

Further Treatment

Rest, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and cortisone injections may be prescribed to reduce inflammation and control the symptoms, but identifying the root cause of TTS helps determine the best treatment. Physical therapy is quite helpful and stretching and strengthening exercises to improve flexibility in the calf muscles encourage the tibial nerve to glide within the TT. Other modalities such as heat, icing, ultrasound and electrical stimulation are also useful.

If conservative approaches fail to relieve the symptoms surgery becomes an option.3 Doctors are slow to consider this as there are risks of tissue damage and there was a history of post-surgical complication. Some procedures involve surgical release of the flexor retinaculum creating more space in the TT as well as removing cysts or other bodies. More recently minimally invasive endoscopic surgeries have proven successful with fewer reported incidents. Post-surgical care involves temporary casting, walking with crutches and a gradual return to activity including exercises to stretch and strengthen the muscles of the lower limb.

Conclusion

TTS usually causes a vague pain in the medial ankle and sole of the foot that patients may describe as a burning, tingling or numb sensation. Frequently the pain increases with activity as a result of squeezing the tibial nerve and worsens as the day progresses.

There are several proposed causes for TTS, but frequently a specific etiology is not identified. It is sometimes seen among athletes and active people who stress the medial ankle area, especially if they stand, walk or exercise for long periods. It may occur as the result of an acute sprain or other traumatic injury and is also associated with chronic medial ankle instability. The goal of treatment is to reduce compression on the nerve relieving the pain, and the symptoms may be reduced with rest.

If the origin of the pain is mechanical, due to pronation, conservative approaches such as foot orthotics, AFO’s and physical therapy are beneficial. If there is an obstruction within the passageway a minimally invasive surgery can be performed to remove it. Other surgeries that release the flexor retinaculum or address nerve impingement at the level of the high ankle are also successful in treating this painful condition. Early diagnosis is important as permanent nerve damage can occur if the condition goes unaddressed.

Séamus Kennedy, BEng (Mech), CPed, FAAOP(A), is president and co-owner of Hersco Ortho Labs, New York. He can be contacted at seamus@hersco.com or by visiting www.hersco.com.

References

- Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome: Expanding the Paradigm on Etiology and Treatment

Michael S. Nirenberg DPM, Roberto P. Segura MD

Podiatry Today Dec 2024 - Recent Advances in Orthotic Therapy

Chapter 8: Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome: Mechanical Origins and Orthotic Treatment

Paul R. Scherer, DPM, MS

Lower Extremity Review, 2011 - Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome – A Comprehensive Review

Ibad Sha, MS, MRCS, DNB

The Iowa Orthopedic Journal. 2024;44(2):32-36