In Greek mythology, Achilles’ mother, Thetis, dipped her young son headfirst into the river Styx to safeguard him in future battle. Holding him by the ankle, she left only his heel vulnerable to injury. The Achilles tendon, the strongest and largest tendon in the body, has always been a common site of injury, including among sports heroes and weekend warriors. In the literature, Achilles tendinopathy has a reported incidence in runners of 6.5-18 percent, but beyond this active population, one-third of the patients who receive the diagnosis are sedentary.1

Achilles Anatomy and Injury

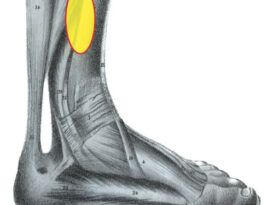

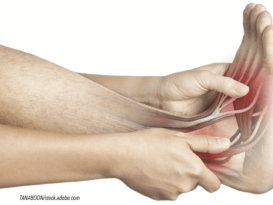

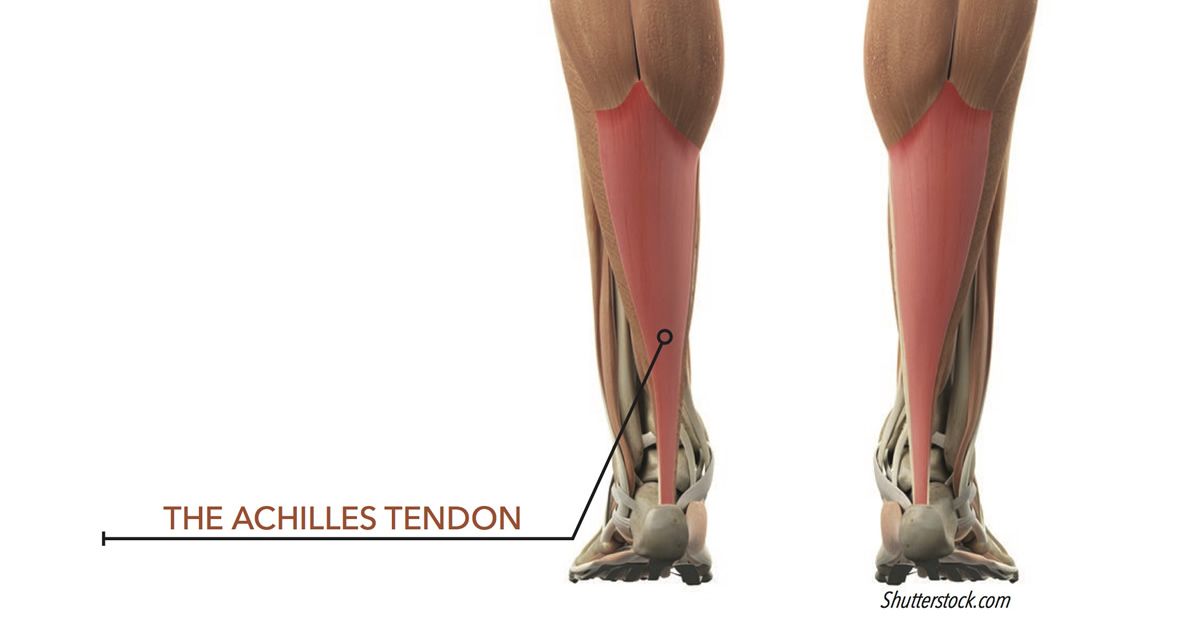

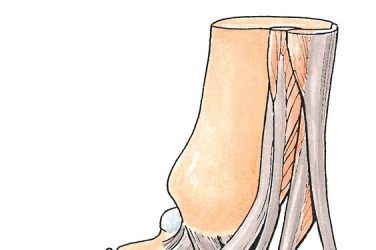

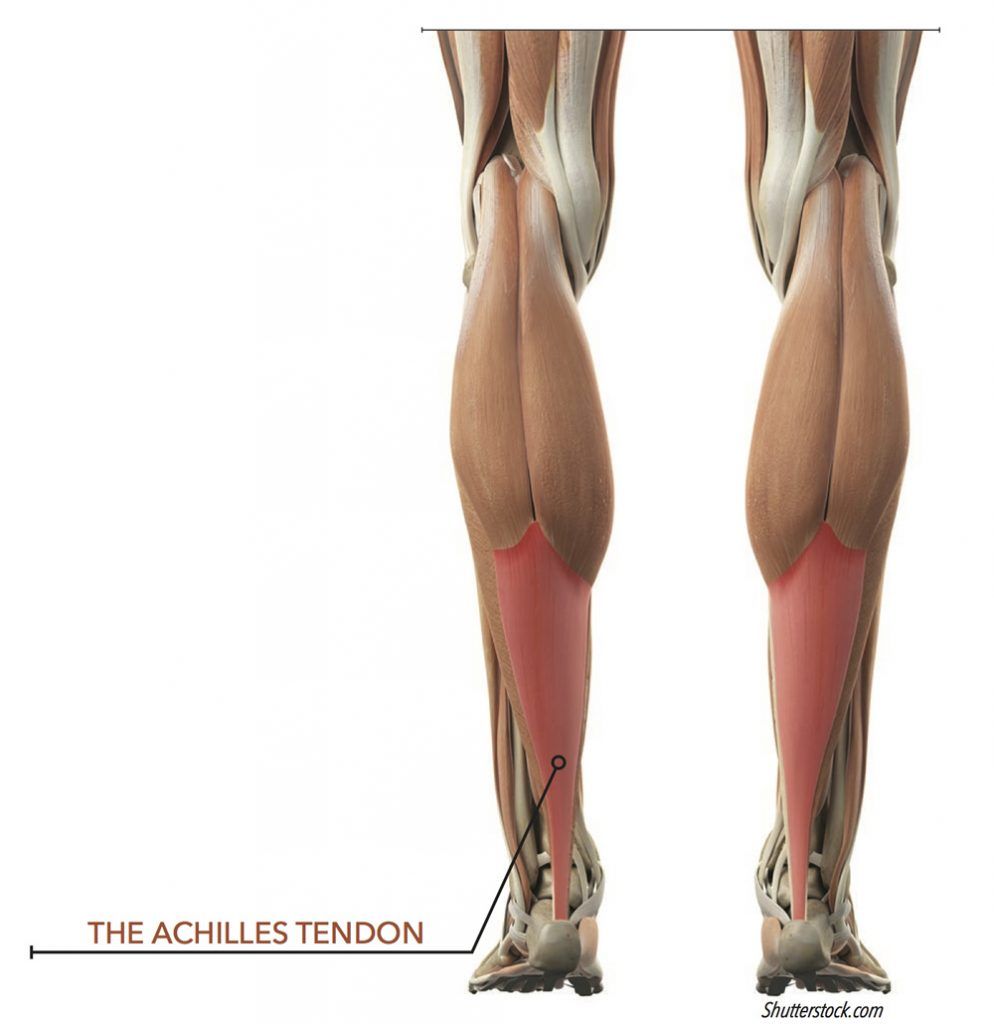

The Achilles tendon, sometimes referred to as the calcaneal tendon, is the continuation of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, the powerful plantarflexors of the ankle. In addition, the gastrocnemius, with its origin above the knee joint, provides knee flexion. These muscles also act eccentrically to control the tibia’s forward motion in gait. The Achilles tendon inserts beneath the subtalar joint (STJ), onto the calcaneal tuberosity, and is often regarded as being contiguous with the plantar fascia. The tendon is narrowest approximately 4cm above the calcaneus, and then fans out distally. This is a region of hypovascularity, and the area of injury most often reported is 2-6cm above the insertion. The tendon also spirals internally, by approximately 90 degrees, as it approaches the insertion. The rotation enhances strength but places the tendon under increased tension. The Achilles tendon lacks a synovial sheath and is surrounded instead with a paratenon of fatty tissue that allows it to glide easily. High-impact athletic activities such as jumping, sprinting, or basketball can subject the tendon to loads of more than six to eight times the person’s body weight.

Historically, most pain or swelling along the lower calf or posterior heel has been referred to as Achilles tendinitis. More recently, the diagnosis has been refined to be more specific to the etiology and location of the pain. The general term used now is Achilles tendinopathy. Achilles tendinitis is an inflammation or irritation of the tendon or paratenon, but histologic studies show it to be less common than previously thought. Tendinosis, on the other hand, is a degenerative process and represents chronic damage to the tendon. Achilles tendon injuries are frequently classified by zone, based on location: insertional, non-insertional (or mid-portion), and proximal (at the muscle tendon interface and above). Injury may result from any combination of overuse, biomechanical abnormality, systemic disease, aging, or prior use of certain medications.

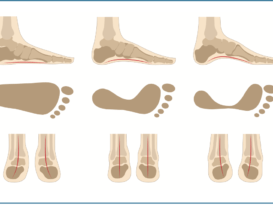

Insertional tendinopathy, an injury at the point of insertion of the tendon into the calcaneus, accounts for less than 20 percent of the incidence rate. However, care must be taken to get a clear diagnosis, because there are several other conditions that can masquerade as pain in this area. A Haglund’s deformity, an abnormal prominence of the posterosuperior calcaneus, can cause heel pain when soft tissue impinges on the heel counter of a shoe. Likewise retrocalcaneal bursitis, an inflammation of the bursa at the posterior calcaneus, can be aggravated by overuse or improper shoes. One should also consider bone stress, such as Sever’s disease in adolescents, or the presence of a bony exostosis or spur as other possible causes of pain. Note that it would not be unusual to find two or more of these conditions simultaneously. Non-insertional tendinopathy is seen along the tendon and paratenon, usually 2-6cm proximal to the insertion. Finally, proximal injury may occur at the muscle tendon junction or within the calf and present as a tendon tear, rupture, or muscle strain. The cause of Achilles tendinopathy is related to a combination of foot type (low or high arch), joint ranges of motion, muscle strength, activity level, and inadequate footwear. In runners, other significant factors include foot strike pattern (rearfoot or forefoot), changes in training intensity, and terrain, such as hills. For example, runners with a rearfoot strike generally put less tension on the tendon at heel strike. In distance runners, recent studies suggest that the strength of the soleus muscle may play a role in the pathology since it protects the Achilles tendon. It is thought if the soleus is weak or if it fatigues, it puts the tendon at risk.

Achilles Tendinopathy Treatment

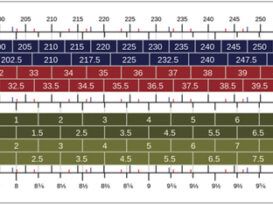

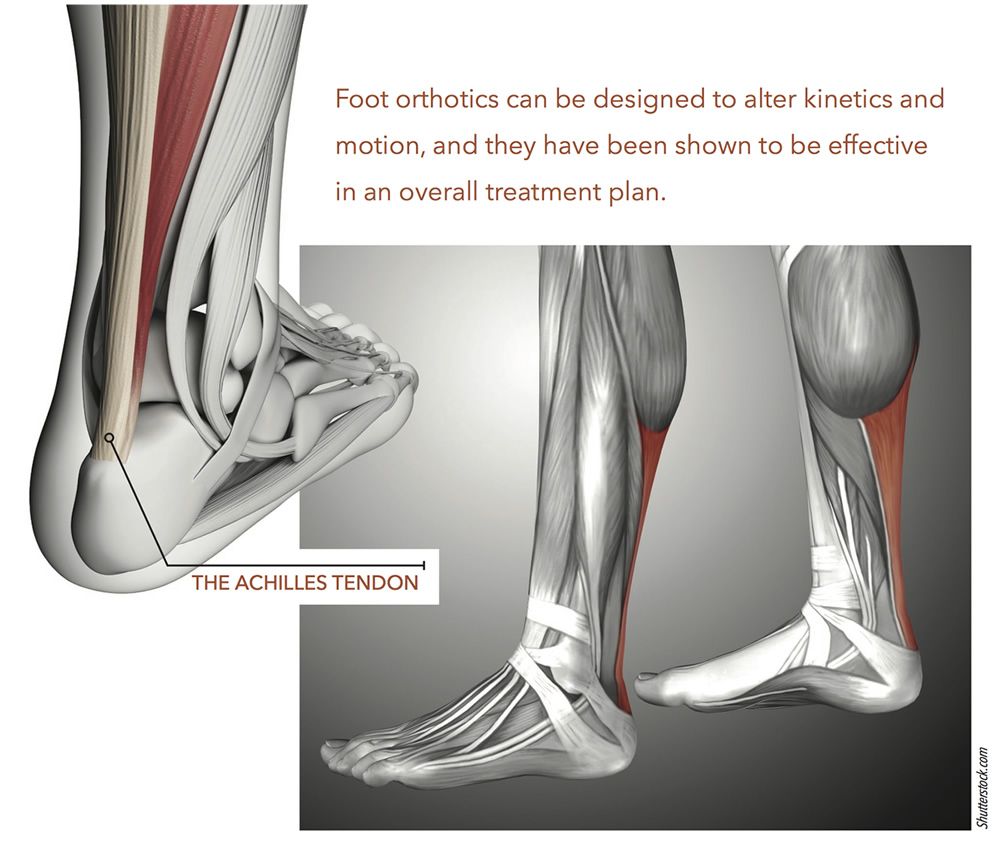

In the acute phase, after a clinician determines there is no tear or rupture, patients should be advised to rest and stretch, and pain-relieving medication may be prescribed. Other treatments such as icing, massage, and ultrasound are often helpful. Any return to activity should be slow and measured, and runners should avoid hills or banked surfaces. One of the more common treatments to relieve strain on the tendon is to provide a heel lift. Elevating the heel by ¼ inch may be sufficient to reduce the stretch on the Achilles and includes the added benefit of plantarflexing the foot, increasing the longitudinal arch. Raising the heel naturally lowers tension on the internally spiraling tendon just as the torque on a twisted cable will be lessened when the ends are brought closer together. These patients should avoid flat shoes or flip-flops. Once the symptoms have been alleviated, it is important to work on the root causes of the problem by improving strength and enhancing biomechanics.

Eccentric stretching and strengthening have been shown to be effective in the treatment of Achilles tendinopathy. Tendons need mechanical loading for healing, and a physical therapist’s skill lies in being able to successively load the tendon—but not to the point of pathology. The Alfredson protocol prescribes 12 weeks of single-leg heel-drops with weights.2 The exercises were originally prescribed twice daily with knee extended and knee flexed, to isolate the soleus, for a total of 180 repetitions. At the outset of the initial study, patients had significantly lower eccentric and concentric calf muscle strength on the injured side, but after treatment all 15 participants were back at pre-injury levels of running activity. With further investigation and refinement, this regimen has been modified to include concentric and eccentric exercises and fewer repetitions.3

The triceps surae and Achilles tendon complex spans three joints to form a system that is integral to walking and running. Taken as a whole, the muscle-tendon unit crosses the knee, ankle, and STJ, setting the potential for competing rotational forces to act along its length. As the foot pronates, the tibia internally rotates, but later in the cycle external rotation of the distal tibia can put a counter force on tissue. Similarly, it is believed that excessive pronation of the STJ can generate a shearing force at the insertion. Foot orthotics can be designed to alter kinetics and motion, and they have been shown to be effective in an overall treatment plan.4,5 Semi-rigid orthotics with deep heel cups and rearfoot extrinsic posts offer control for the foot, limiting eversion and enhancing the timing and duration of pronation. It is easy to incorporate a heel raise onto an orthotic and then gradually remove it over time as the tendon heals. It is also important to wear well-fitting and appropriate shoes that provide stability and support for the foot and orthotic.

Achilles tendinopathy can be a chronic condition that severely limits the activities of otherwise active and fit individuals. It is classified by specifying the location and the nature of the pathology. Although the etiology may be multifactorial, there is a significant body of research to show it can be conservatively treated with a combination of rest, physical therapy, and improved biomechanics.

Séamus Kennedy, BEng (Mech), CPed, is president and co-owner of Hersco Ortho Labs, New York. He can be contacted at seamus@hersco.com or by visiting www.hersco.com.

References

1. Nunley, J. A., editor. 2009. The Achilles tendon: treatment and rehabilitation, Springer, New York.

2. Alfredson, H., T. Pieta, P. Jonsson, R. Lorentzon. 1998. Heavy-load eccentric calf muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. American Journal of Sports Medicine 26(3):360-6.

3. Silbernagel, K. G., K. M. Crossley. 2015. A proposed return-to-sport program for patients with midportion Achilles tendinopathy: rationale and implementation. Journal of Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy 45(11):876-86.

4. Mayer, F., A. Hirschmüller, S. Müller, M. Schuberth, H. Bar. 2007. Effects of short-term treatment strategies over 4 weeks in Achilles tendinopathy. British Journal of Sports Medicine 41(7).

5. Sinclair J., J. Isherwood, P. J. Taylor. 2014. Effects of foot orthoses on Achilles tendon load in recreational runners.Clinical Biomechanics 29(8):956-8.