Leg length discrepancy (LLD) is a diagnosis that appears deceptively simple, one limb being shorter than the other. However, there is more to the apparent difference in limb length than meets the eye, and sometimes an almost imperceptible difference can be the cause of issues that arise anywhere along the lower limb or in the back.

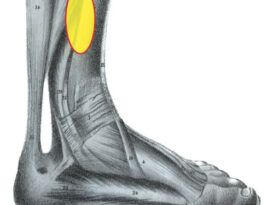

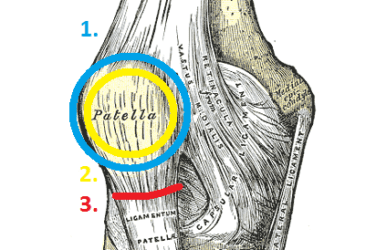

The sacrum sits between the ilium supporting the lumbar spine, and imbalance distal to this can be a source of lower back pain. Symptoms can be diverse and vague, such as complaints of lower-limb pain, intermittent backache, uni- lateral foot pain, or a nagging, recalcitrant running injury. Interestingly, the majority of people have some small amount of LLD, although it frequently remains asymptomatic as most can adapt and compensate for it.

Etiology

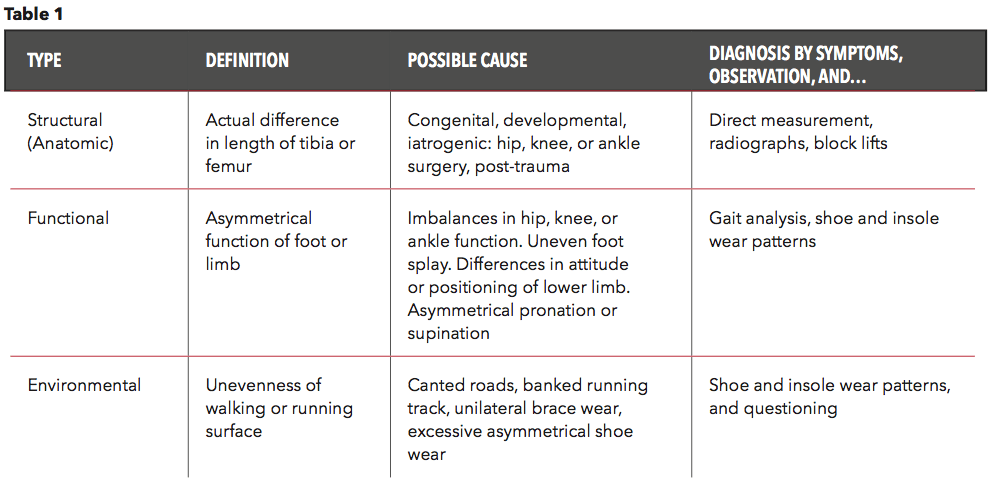

Traditionally LLDs have been divided into several distinct categories but there is overlap among them and it is not unusual to have a patient present with more than one type (Table 1).

Structural LLDs are the result of an anatomic short limb—an actual difference in the length of the tibia or femur. These may occur due to congenital or developmental factors. They may also be the result of trauma, post-polio syndrome, or other conditions that create an LLD that needs to be actively managed. Iatrogenic deformities, the result of medical treatment, also fall into this group. Imbalances created from common hip and knee replacement surgeries can leave patients with structural LLDs.

Functional LLDs, due to a functional difference in biomechanics, are the result of compensations or restrictions. For example, unilateral muscular weakness or inflexibility, restricted ranges of motion at the ankle, knee, or hip, or anomalies of the pelvis can all lead to compensations that manifest as an LLD. Although functional in nature, these discrepancies can be just as serious and lead to chronic pain that limits a patient’s activity level or an athlete’s participation in sport.

Environmental LLD is a third group caused by external factors. For example, road runners are encouraged to train on the left-hand side of the road, facing oncoming traffic for safety reasons, but crowned paved surfaces create an apparent LLD—the right leg will be effectively longer than the left. Some gyms with banked tracks try to negate this phenomenon by encouraging runners to reverse their direction every other day. Excessive uneven wear on shoe soles can also be a contributing factor to an environmental LLD. Finally, unilaterally dispensing an AFO, post-op shoe, or any brace may create an unintended LLD.

Examination

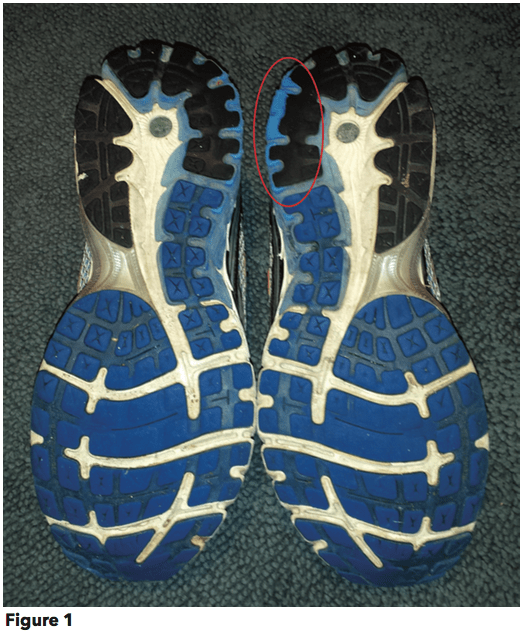

Observation of an asymmetry, whether in stance, gait, foot type, or shoe wear pattern, is a clue that some form of LLD may be present (Figure 1). Typically, the center of gravity shifts to the short limb side and patients display indications such as head tilt, shoulder or pelvis imbalance, or lumbar scoliosis. On the long side you may notice knee flexion or unilateral pronation. Asking simple questions such as, “Do you favor one leg over the other?” or “Do you find it uncomfortable to stand?” may also provide valuable information.

Performing a gait analysis will yield clues as to how a patient compensates during ambulation. Regarding arm swing it has been observed anecdotally that “the short side swings more.” Another tell-tale sign is uneven head rise due to vaulting on the long leg side. Computerized gait analysis with in-shoe sensors or floor pressure mats can indicate load and timing differences between each side.

Usually the long side will have extended stance while the short side may go into early heel rise. Gait can also be video recorded and played in slow motion to catch more subtle aspects of movement. Compensations for an LLD can occur across many body segments and in all three planes, so it is vital to keep a wide view.

The Pronation Test

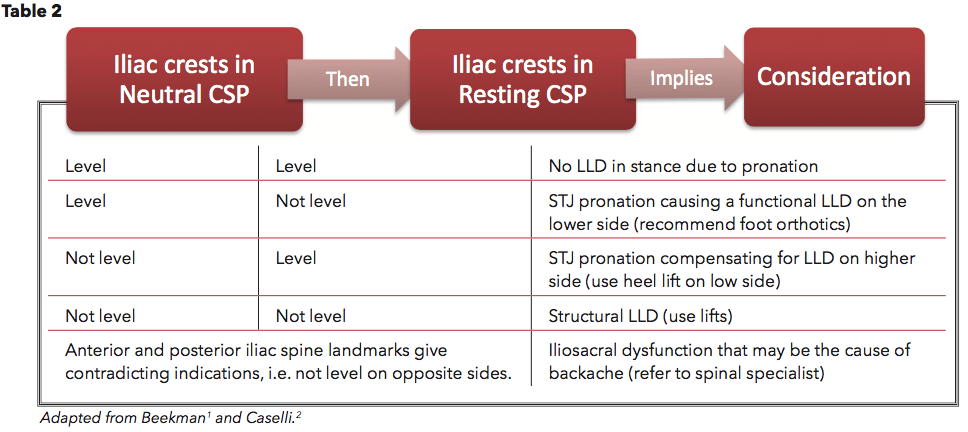

The pronation test is a valuable clinical tool for determining the contribution of foot position and isolating the nature of an LLD. With the patient standing in his or her regular angle and base of stance, have him or her move into subtalar joint (STJ) neutral, creating a near vertical calcaneus. This is known as neutral calcaneal stance position (NCSP). With your arms extended, palpate the iliac crests (ICs) with your thumbs and note their relative height as being either level or unlevel. Then have the patient relax or pronate into a resting calcaneal stance position (RCSP).

If the ICs remain level in both foot positions, then there is no LLD due to pronation. However, if the ICs are even in the neutral position but become uneven in the relaxed position, then STJ pronation is causing a functional LLD on the lower side. In this case, foot orthotics that rectify the pronation will be very beneficial. If the ICs are not level in the NCSP but become level in RCSP then STJ pronation is likely compensating for the anomaly and a lift on the short side will help address the problem. If the ICs remain uneven in both the neutral and resting positions, it indicates a structural LLD requiring a lift or shoe modification. Lastly, the observation of uneven anterior and posterior IC heights that contradict each other, left side to right side, signifies iliosacral dysfunction that may be the cause of back pain (Table 2).

Measurement

It is vital that practitioners measure the LLD for themselves and not rely on a patient account or a previous lift. Measuring for an LLD is not an exact science; there is no clinical consensus as to which anatomical references should be used or how the patient should be positioned. In addition, direct measurement results, with a cloth tape, can be difficult to reproduce across practitioners and only indicate a structural LLD. It may be best to use several methods to develop a composite picture.

One approach to direct measurement of structural LLDs is to measure from the anterior superior iliac spine to the distal aspect of either the medial or lateral malleoli. This measurement approximates the actual limb length difference but fails to account for irregularities below the ankle such as equinus or plantarflexion contractures. Radiographs can provide a more accurate assessment and measurement of structural differences.

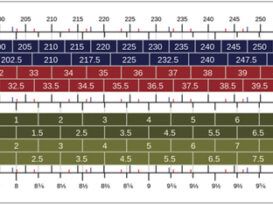

Indirect measurement is a simple and effective way to evaluate the amount of lift that makes a patient comfortable and to gauge how much they can tolerate. With this method you are measuring the correction—not the discrepancy. Use a series of blocks or sheets of firm material (cork or neoprene) of varying thickness, e.g. 1/8 in., 1⁄4 in., and 1⁄2 in. Place them under the short limb, either under the heel or the entire foot depending on the mechanics, until the patient feels most in balance or level.

Correction

There is no agreement as to the amount of measured difference that should trigger an intervention. Primary considerations include the presence of symptoms or dispensing a unilateral AFO. There is some consensus that for LLDs greater than 1⁄4 in. (6mm), and especially for athletes, some form of treatment should be attempted, although often cases greater than this can be asymptomatic.

Usually it is not appropriate to correct for the full measured amount of an imbalance at the outset. The longer a patient has had the LLD the less likely he or she will be able to tolerate a complete correction immediately. This is a process of incremental improvements. It is quite possible that the initial lift will need to be augmented as the patient’s musculoskeletal system adjusts. It is often recommended that the first build up approximates 50 percent of the total. After a suitable break-in period, one month for example, another 25 percent can be added. If warranted more can be provided later.

Once you determine how much lift the patient can tolerate, you then need to decide how best to apply it. There are advantages and disadvantages to using either internal or external lifts.

Internal Lifts

Putting a simple heel lift inside the shoe or onto an orthotic has the advantage of being transferable to many pairs of shoes. It is also aesthetically more pleasing as the lift remains hidden from view. However, there is a limit as to how high the lift can be before affecting shoe fit. Dress shoes will usually only accommodate small lifts (1/8-1⁄4 in.) before the heel starts to piston out of the shoe. Sneakers and work boots may allow higher lifts, perhaps up to 1⁄2 in., before heel slippage problems arise. Room permitting, it is helpful to extend the lift beyond the heel pad to avoid gapping under the arch and to support the foot more fully.

External Lifts

If a lift of more than 1⁄2 in. is required, consider adding to the outsole of the shoe. Although some patients may worry about the cosmetics, it does ensure better overall fit and function. With the development of synthetic foams and crepes, lifts do not have to be as heavy as the cork and leather buildups of the past. External buildups are not transferable, and they will eventually wear down, so the patient needs to be vigilant in having them repaired. In cases requiring small changes, platform shoes or certain women’s high heels can be adjusted lower on the opposite side and thereby correct the imbalance.

Compromise is always a worthy attribute and a blend of both internal and external lifts often works well when more than 1⁄2 in. is necessary. In this way the shoe fit is not much affected yet changes to the overall look are minimized. A follow-up gait analysis should reveal a more symmetric gait, more even pressure distribution across both feet and hopefully an eventual lessening of painful symptoms.

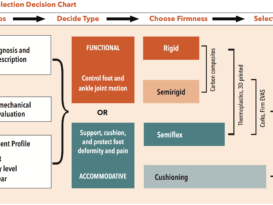

Foot orthotics can correct unilateral pronation, include heel lifts, and rebalance foot function by incorporating wedges and cut outs. Physical therapy can also play a role in addressing muscle and joint discrepancy and regaining functional equality.

Conclusion

In assessing LLDs it is important to remember that they result from more than a single contributing factor. Regardless of origin, the presence of even a small difference may be sufficient to develop pathology, especially in runners and athletes. Evaluating LLDs and noting asymmetry in gait is an important aspect of every patient’s overall biomechanical exam. Once identified, it is possible to use a range of conservative approaches including internal lifts, shoe elevations, orthotics, and physical therapy exercises to address abnormal function and return the patient to pain free activity.

Séamus Kennedy, BEng (Mech), CPed, is president and co-owner of Hersco Ortho Labs, New York. He can be contacted via e-mail at seamus@hersco.com or by visiting www.hersco.com.

References

- Beekman, S. 2007. Asymmetry and the Athlete. Podiatry Management 26(4): 79

- Caselli, M. 2006. Evaluation and Management of Leg-length Discrepancy. Podiatry

Management. - D’Amico, J. 2014. Keys to Recognizing and Treating Limb Length Discrepancy. Podiatry

Today 27(5): 66-75.