Few words on foot orthotic prescriptions cause as much confusion as the term Morton’s. Morton’s is simultaneously two different foot diagnoses, and three or more distinct orthotic modifications. One misunderstanding stems from the fact that two esteemed doctors, both named Morton, applied their names to unique foot pathologies.

Morton’s Syndrome

Dudley Joy Morton, MD, was a prolific early 20th century physician who developed the concepts behind Morton’s syndrome. This is characterized by a congenitally short first metatarsal bone, hypermobility of the first ray, and callusing under the ball of the foot, specifically at the second and third metatarsal heads. The shorter first metatarsal, and its lack of dorsiflexion stiffness, cause excessive weight to be borne by the second metatarsal head resulting in callus formation. Pain and tenderness are usually felt at the base of the first two metatarsal bones and at the head of the second. This short first metatarsal, relative to the lesser metatarsals, is the most easily recognizable attribute and often results in the second toe appearing longer than the hallux. The appearance of a longer second toe was commonplace in classical Greek sculpture, so this is sometimes referred to as Greek toe.

Typically, patients will seek treatment when there is persistent pain or discomfort either at the base of the first two metatarsal bones, or at the heads of the second and third. Conservative treatment of Morton’s syndrome consists of adding a flexible platform or wedge under the first metatarsal and great toe to increase the ground reaction force (GRF) there. By “bringing the ground up” to the first metatarsal, the first metatarsal is assuming extra weight, thereby relieving some of the load on the second. This addition of extra mate- rial to the medial-distal portion of a foot orthotic is called a flexible Morton’s extension (Figure 1a). It can be made of cork, EVA, or other suitable materials, and is usually 1/8-3/16 inch thick.

Functional Hallux Limitus

Other conditions require decreasing the load at the first metatarsophalangeal joint (1st MPJ) to increase the joint range of motion (ROM). Functional hallux limitus occurs when there is a blocking of motion and the great toe is unable to dorsiflex at the first MPJ. This may cause pain and joint deterioration, and it interferes with the pre-swing phase of gait. Patients will often shift weight to the outer border of the foot to prevent painful motion in the big toe.

While the patient is seated and non- weight bearing, check the first MPJ ROM in the sagittal plane by flexing and extending the hallux. Unloaded, there should be 65 degrees of dorsiflexion available. Then load the first metatarsal head with your thumb, repeat the test, and note any restriction. It is not unusual to see a significant decrease in dorsiflexion. This gently simulates the GRF acting on the medial foot during midstance and terminal stance.

TABLE 1: MORTON’S EXTENSIONS

|

TYPE |

EFFECTS |

INDICATIONS |

|

FLEXIBLE |

Increases GRF under first MPJ and hallux. Increases weight borne by first metatarsal. May limit motion of the first MPJ |

Morton’s syndrome |

|

REVERSE |

Decreases GRF under first MPJ and hallux. Decreases weight borne by first metatarsal. Designed to increase motion of the first MPJ |

Functional hallux limitus Plantarflexed first metatarsal. Turf toe, early stage Plantar fasciitis Sesamoiditis (with dancer’s pad) |

|

RIGID |

Decreases ROM along first MPJ and hallux. Tends to impede gait |

Hallux limitus (advanced). Hallux rigidus (with rocker sole). Turf toe |

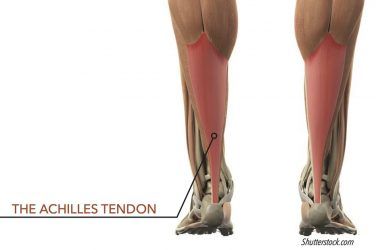

A reduction in motion indicates a restriction of the first MPJ at a critical moment in gait and some level of functional hallux limitus. This could obstruct the Windlass mechanism or lead to an impeded gait. Often there will be a pinch callus on the medial hallux and eventually perhaps arthritis of the joint.

Performing the weight bearing Hubscher maneuver tests the functional ROM of the first MPJ. With the patient standing in the resting calcaneal stance position, dorsiflex the hallux and note motion at the joint. Less than 12 degrees of dorsiflexion indicates a functional hallux limitus and a restriction of the Windlass. The Windlass mechanism is essential for pulling the plantar fascia taut and stabilizing the midtarsal joint during the propulsive phase of gait.

An effective approach to early stage functional hallux limitus is to provide a reverse Morton’s extension on a supportive orthotic. The goal is to increase ROM at the first MPJ. In general, good medial longitudinal arch support helps orient the first metatarsal bone, aligning the first MPJ for optimal function. A reverse Morton’s can take two forms.

A channel or trough distal to the first metatarsal head allows it to plantarflex (Figure 1b). Alternatively, a platform of 1/8-inch flexible material, albeit a little more bulky, can be used to elevate the second through fifth metatarsals, transferring load laterally (Figure 1c). In either case the objective is to shift GRF locally and allow the first ray to plantarflex, which reduces compression forces in the joint. The prescription may also include a low, broad metatarsal pad. Other conditions such as plantar fasciitis, turf toe, and sesamoiditis can also benefit from this style of modification.

Hallux Rigidus

Hallux rigidus is characterized by pain and stiffness in the first MPJ both when the patient is weight bearing and non-weight bearing. There are several techniques available to limit ROM in the forefoot. A rigid Morton’s extension is a foot orthotic design where the rigid shell material extends distally under the first MPJ to the tip of the hallux. It is usually made of rigid thermoplastic or carbon graphite materials (Figure 1d). This device may impede gait, and if the extension is not fully rigid it may even exacerbate the condition. If the goal is to eliminate ROM, then it may be preferable to add a sole stiffener to the shoe or place a full-length carbon foot plate under the insole of the shoe. Full-length foot plates have the added advantage of being transferable between shoes. In addition, putting a rocker sole or rocker bar on the shoe will help reduce metatarsal flexion.

Morton’s Neuroma

In the 19th century, several prominent surgeons studied neuralgia of the forefoot, and Thomas G. Morton bequeathed his name to entrapment neuropathy of interdigital nerves. Morton’s neuroma is a painful condition that occurs most frequently at the distal end of the third intermetatarsal space (between the third and fourth metatarsals), but it can also be found in other interspaces. The entrapped and damaged nerve causes a sharp burning and aching of the forefoot. Patients often describe the feeling of a pebble or small stone inside the shoe. The pain is plantar to the metatarsal head and may radiate distally along the sides of affected toes. In the mid-20th century it was confirmed that Morton’s neuroma pain was the result of swelling or thickening, a benign tumor of the interdigital nerve at the junction where it branches out to individual toes. There are several theories as to the cause, including repetitive trauma, proximity to the intermetatarsal ligament, and nerve enlargement in older patients; all of which result in irritation of the nerve. Care must be taken to make a proper diagnosis as other conditions such as bursitis, capsulitis, and metatarsalgia in general can present with similar symptoms.

Morton’s neuroma pain is far more common in women than men, and it is aggravated by wearing shoes that are too tight or narrow in the forefoot. Patients can get relief when walking barefoot, and wearing wide, comfortable, low-heeled shoes is often a first step in resolving the complaint.

The most conservative treatment is to apply a metatarsal pad directly into well-fitting shoes. By supporting the transverse arch and spreading the metatarsal heads, the compression on the nerve will be reduced. Foot orthotics with metatarsal pads are beneficial because they can be moved between shoes and help by providing stability to the foot, curtailing excessive motion. When a metatarsal pad or foot orthotic is provided, it is important that the patient wear wider shoes, especially in the toe box, otherwise the pain will worsen as bulk is added to an already tight fit. Alternatively, providing a drop or relief under the metatarsal head may be sufficient to relieve some of the pressure. Torpedo-shaped neuroma plugs are also sometimes used, but their placement needs to be very accurate to get good results. Other medical treatments include medications and local injections. If conservative treatment fails, surgical excision may be indicated

Séamus Kennedy, BEng (Mech), CPed, is president and co-owner of Hersco Ortho Labs, New York. He can be contacted via e-mail at seamus@hersco.com or by visiting www.hersco.com.