There are conflicting opinions within the medical community regarding when it is appropriate to treat pediatric flatfoot. This has been an ongoing conversation that vacillates between the poles of conservative early intervention or taking a wait-and-see approach. Part of the issue and lack of consensus stems from a dearth of well-documented evidence to support either extreme.

For anyone working with children in the orthopedic domain it is very important to understand what is at stake. Decisions made about children’s health during their critical early development may not be apparent for years or even decades, and often the full results are realized only as adults. Given the extended life expectancy of children born today coupled with future advances in medicine, many of them will be hoping for a century of walking. Quality of life in the elderly is very much related to foot health and an absence of foot pain. In much the same way that bracing for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis has been shown to decrease curve progression, it behooves us as a profession to promote good foot health in children.

One factor obscuring the issue is the broad nature of the term flatfoot and the absence of a clear definition. A review of the literature shows vastly different estimates of the incidence of pes planus in children. Some studies categorize the feet by external appearance, others by calcaneal angle and a few rely on radiographs. As a child’s foot structure changes rapidly in the first 7 years of life, comparative studies must be age specific. In a previous article, Considerations in the Development of the Lower Limb in Children (The O&P Edge Nov. 2018, https://hersco.com/education-center/development-of-the-lower-limb-in-children/ ) it was noted that the foot of a new born is encased in fatty tissue, and upon weight bearing there is the appearance of a pes planus. This may not be a true flatfoot, just the arch morphology lost in a bulbous shape. Usually the calcaneus in infants is everted but during normal development this eversion reduces by approximately 1o per year. A helpful rule-of-thumb to calculate acceptable calcaneal eversion in the early years is to subtract the child’s age from 7. For example, a normal 4 year old would have 3o of eversion (as 7 – 4 = 3 ), and by the age of 7 – 8 the calcaneus should be near vertical ( 7 – 7 = 0 ).

Current guidelines from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons ( https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/flexible-flatfoot-in-children ) include, “..most children eventually outgrow flexible flatfoot without developing any problems in adulthood. The condition is usually painless and does not interfere with walking or participation in sports. If your child’s flexible flatfoot does not cause pain or discomfort, no treatment is needed”. Whilst this may be true for many children we need to be cautious in interpreting such a general statement as applying to all children.

Subgroups

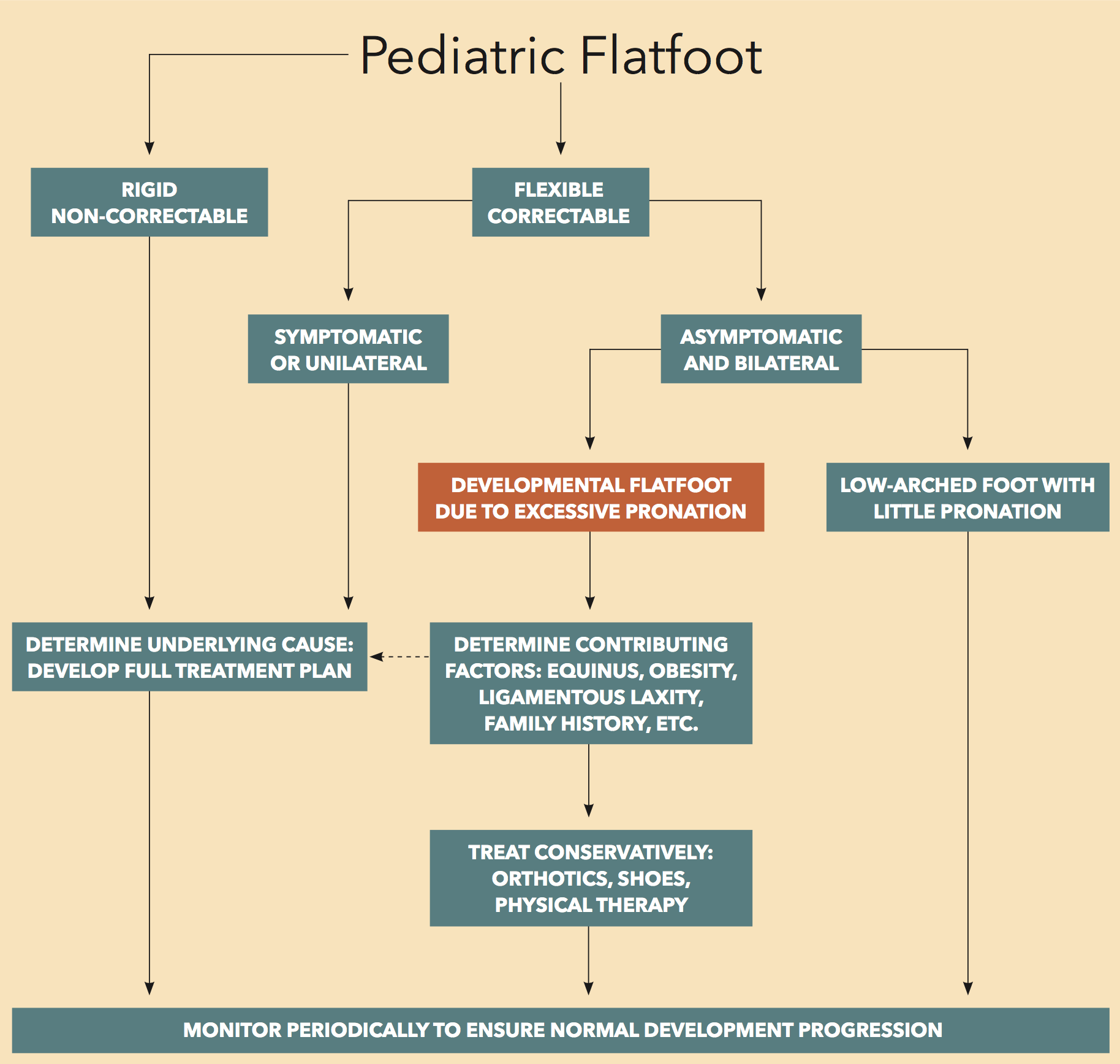

An initial step is to recognize not all flat feet are equal: they can be categorized into proper sub-groups. The first major distinction is between rigid and flexible. A rigid flatfoot is one that remains flat both non-weight bearing and weight bearing. The foot shape is not correctable and there is a significant limit or absence of motion. Rigid flatfeet in children can result from many issues including osseous coalitions or a vertical talus which require specific investigation and diagnosis. Doctors will evaluate, determine the cause and treat these cases based on the patient’s age, prognosis and surgical options. A second factor to consider is pain: the symptomatic versus the asymptomatic foot. Most physicians and parents will readily treat the symptomatic foot especially if the child is avoiding activity to limit pain or discomfort.

However, addressing both of these categories still leaves by far the largest segment of the group – children with an obvious flatfoot but no discernable issues at present. The question is: Will they out grow it? Or is it a seed problem that will manifest later in life? Studies show there is a high correlation between flat feet in adults and common foot problems such as Adult Acquired Flatfoot, Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction and Hallux Valgus. In addition, the foot supports the superstructure of the body and excessive pronation in adults has been directly linked to compensations and pain at the knee, hip and lower back. How much of this could be avoided by early intervention, tackling the root cause?

Developmental Flatfoot

With experience skilled practitioners can learn to distinguish a flat foot, that is a foot with no arch or a low arch, from a developmental flatfoot. A low arched foot may be properly aligned and not exhibit any signs of pronation. On the other hand, for children 6 years or under, a developmental flatfoot is one that demonstrates excessive pronation while weight bearing. Pronation is tri-planar, critically affecting motion in the foot and ankle, and also more subtly further up the lower extremity. When the SubTalar Joint pronates the calcaneus everts and the MidTarsal Joint opens. This sequence collapses the arch and one may notice some or all of the following: navicular drop, medial prominence of the talar head, forefoot abduction, or a concavity along the lateral border of the foot. None of these signs should be considered normal.

Developmental flat feet appear normal when non-weight bearing but collapse once the child stands. It has also been referred to as hypermobile foot and it presents bilaterally. Unilateral presentation requires further investigation and issues such as a leg length discrepancy should be considered. It is important to note arch height alone is an unreliable indicator, but excessive pronation is abnormal at any age. A full description of this foot type is detailed in a series of articles by Dr. Joseph D’Amico1, DPM.

Although a child may be able to tolerate such an everted position – presenting as asymptomatic – it is firmly believed that repetitive stresses acting on this vulnerable foot will lead to pathology. Both Wolff’s Law (bone growth in response to force) and Davis’s Law (soft tissue modeling to imposed demands) support this assumption. Forces on the immature and mal-aligned osseous structure plus strain on ligaments, muscles and tendons will result in a host of compensations. Underscoring this point, it has been documented that overweight children have a higher incidence of flatfoot and there is valid concern that childhood obesity may lead to foot problems in adulthood2.

Evaluation

The decision whether to treat or not should be based on a thorough biomechanical examination that includes: checking joint Ranges of Motion and ligament integrity; measuring varus components of the lower leg, rearfoot and forefoot; testing muscle strength, etc… When working with children it is always important to be aware of other systemic disorders and neurologic conditions that may contribute to flat feet. The clinician must also check for equinus as pronation in young children can often be a compensation for restriction in ankle motion. Equinus is recognized as the inability of the neutral foot to dorsiflex to 90 degrees as the result of a either a tight heel chord or a boney block. Parents should be questioned regarding their own history and prevalence of flatfoot within the family, and the child’s possible avoidance of play, walking or exercise. Concern with any of these factors are cause for further evaluation.

Within the academic podiatric community it is believed that children with developmental flatfoot should receive early treatment to align their foot structure to a normal position. Limiting excessive pronation and providing support for the SubTalar Joint with the use of functional orthotics – prefab or custom – limits the destructive forces acting on the open, malleable foot. Not all children with flexible flatfeet need orthotics but they should be monitored closely. If they are going to “outgrow it” the practitioner should periodically track consistent changes in the key indicators of calcaneal angle, arch height, medial convexity and forefoot abduction. If excessive pronation remains persistent consider taking proactive measures. Children’s feet go through a golden age where conservative treatment encourages normal development, setting them up for a lifetime of good exercise habits and pain free walking.

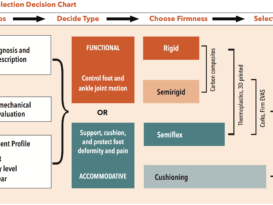

Designing Foot Orthotics for Children

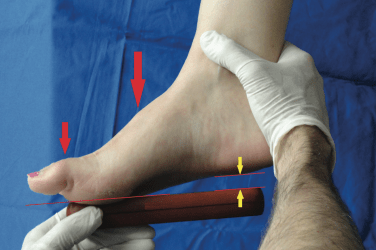

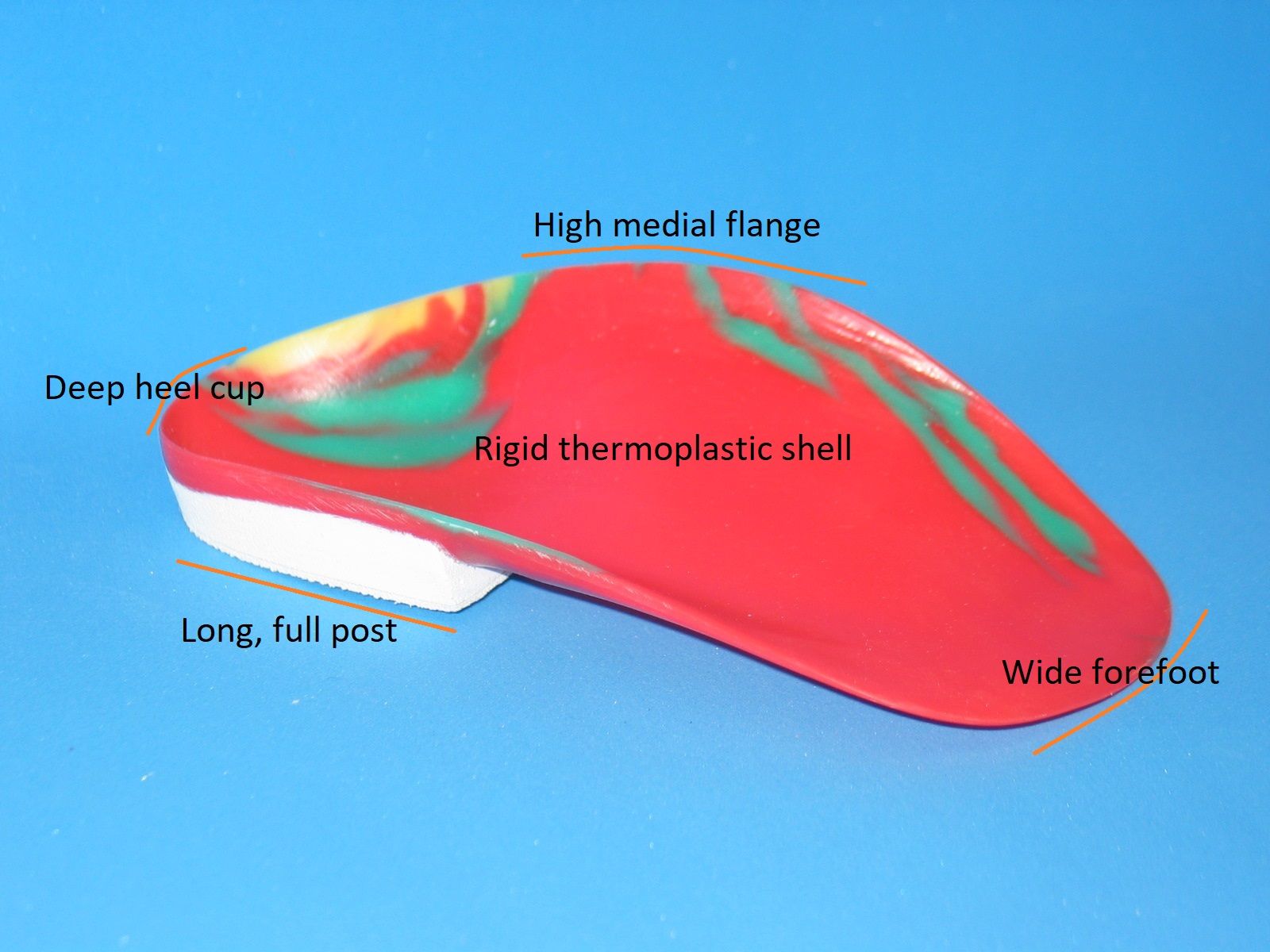

Foot orthotics are often prescribed for children with flexible flatfoot. The UCBL is the classic children’s foot orthotic design, offering very rigid control and heel walls extended up to 35mm. Many of its features can be incorporated into any child’s orthotic. There are several characteristics of good functional devices that should be considered for the pediatric population3.

Good Cast. It is vital to take a good cast of the foot. Depending on the age of the child, and their receptivity to the process, this can sometimes prove difficult. Whilst a plaster slipper cast is ideal, it may not be always possible. Even scanning may not work if the child cannot hold still for the short length of time it takes to capture a good image. Impression foam is the most widely used method and delivers good results when the cast is taken with care and the corrected foot position is maintained. Allowing the child to participate in the process sometimes helps. For example, having them push their hand into the foam can catch their attention. Other times, if they are left to play on an electronic device they may be quite content to let the practitioner work with their feet.

Minimal Arch Fill. Assuming the cast is good, and it represents the corrected arch, have the lab maintain the child’s foot shape. The orthotic will then hold the foot in that ideal position when they are weight bearing.

Rigid Shell. The shell should be sufficiently rigid to control the foot. Children with flexible feet easily tolerate the support and gain the benefit of the corrective alignment.

Deep Heel Cup. All devices for children should have a deep heel seat. The hallmark of developmental flatfoot is excessive pronation and calcaneal eversion. A deep heel cup will help hold the SubTalar Joint closer to the neutral position. Depending on foot size the wall height should be anywhere from a minimum of 10mm to >18mm +.

Full Width. The distal end of the orthotic should be kept wide to offer full support and stability, maintaining the medial column of the foot. Unlike adults, who often wear narrow shoes, most children have roomy sneakers with removable inlays that can accommodate a wider shell.

Medial Flange. Include a medial flange in the design to fully support the longitudinal arch. Although adults often complain about a medial flange due to “edge pressure”, especially at the navicular, children’s feet are far more flexible. Up until the age of 6 the navicular is not yet fully formed. Providing a medial flange increases the surface area and thus the effectiveness of the device.

Medial Heel Skive. Adding a Kirby heel skive to the positive cast increases the ground reaction force in the rearfoot and helps counter calcaneal eversion assuming the heel cup walls are deep enough.

Full Posts. Rearfoot posting should be both long and wide. Full posts that are not beveled or angled inwards make the orthotic more stable and offer better control in the hindfoot.

No Top Cover. Children frequently delaminate top covers and can quickly outgrow the length, even though the underlying device remains effective in controlling pronation. Consider dispensing the orthotic without any top cover.

Given the rapid changes that occur in the size and shape of a growing child’s foot it may not be necessary or feasible to provide custom orthotics. There are several brands of over-the-counter functional children’s orthotics that meet many of the criteria listed above. Studies have shown that children benefit from the support and control offered by well designed, stable prefabs. Custom orthotics are prescribed where prefabs are not specific enough for the case or the cause of the complaint. Well fitting corrective shoes can also be helpful in guiding the growth of the young foot.

Séamus Kennedy, BEng (Mech), CPed, is president and co-owner of Hersco Ortho Labs, New York. He can be contacted via e-mail at seamus@hersco.com or by visiting www.hersco.com.

The author gratefully acknowledges the help and contribution of Joseph C. D’Amico DPM, DSc in preparing this article.

References

1. D’Amico. J. 2018. Developmental Flatfoot Parts 1 and 2. Podiatry Management.

2. Scherer, P. 2009. The Obesity Epidemic in Children Is Causing Flatfeet. Podiatry Management.

3. Scherer, P. 2008. Treatment of Pediatric Flexible Flatfoot with Functional Orthoses. Podiatry Management.