Urgent concern regarding diabetes is not only a health issue in the United States but it is a global epidemic easily affecting half a billion people. A host of factors from less active lifestyles, diets high in sugar and refined foods, and a general trend towards obesity has led to a dramatic increase in the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and foot ulcers. Among its many long-term effects, diabetes leads to peripheral neuropathy, making the foot susceptible to ulceration. Diabetes is the pathway for the majority of non-traumatic lower-limb amputations in the United States. According to statistics from the World Health Organization, diabetes mellitus is the seventh leading cause of death globally.

Management of the Diabetic Foot

Since the mid-1990s, the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) has published evidence- based guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetic foot disease. Their reports, seven in all, include updated guidelines based on current research from studies and meta-analyses. They employ well- established methodologies to conduct systematic reviews of the most recent literature and from that develop recommendations for off-loading and preventing diabetic foot ulcers and amputations.

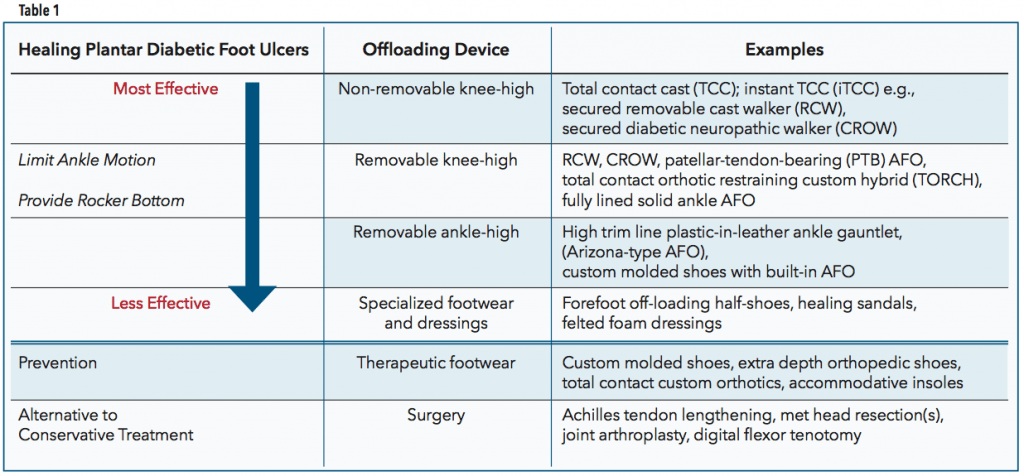

Their recommendations for healing a neuropathic plantar forefoot or midfoot ulcer in a person with diabetes can be summarized in several choices of treatment (Table 1). The first choice of treatment is a non-removable knee-high offloading device. This should incorporate an appropriate foot-device interface to alleviate and redistribute pressure. If contraindications such as infection, ischemia, or patient intolerance to non-removable devices exists, then removable knee-high and removable ankle-high off-loading devices are to be considered as the second and third choice off-loading treatment, respectively. Appropriately fitting footwear combined with felted foam is the fourth choice but should only be considered when none of the previous options are possible. If these nonsurgical, conservative off-loading approaches fail, only then should surgical interventions be considered for healing metatarsal head and digital ulcers. There are other specific guidelines for cases when infection or ischemia are present.

Patients with plantar heel ulcers should also consider using knee-high off-loading devices or other interventions to reduce plantar pressure on the heel. Finally, to heal non-plantar foot ulcers it is recommended to use ankle- high devices, footwear modifications, toe spacers, or orthotics.

Biomechanics of Breakdown

Although diabetes is a metabolic disease, the development of a plantar foot ulcer can be considered biomechanical in nature. In normal gait the heel contacts the ground first and as gait progresses the body passes over the plantigrade foot. The stance leg and foot accept the full load of body weight as the contralateral limb goes through swing. One of the requirements for smooth and asymptomatic ambulation is fluid and free joint motion, especially at the ankle and first metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ).

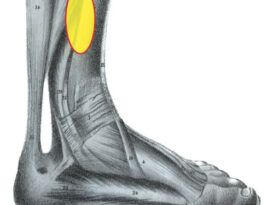

One of the side effects of diabetes and uncontrolled blood sugars is the process of glycosylation, an irreversible cross-linking of collagen and keratin. This causes a thickening of the skin, tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules. It leads to a reduction in joint flexibility and motion, termed limited joint mobility (LJM), leaving the tissue compromised. If, as a result of glycosylation, the necessary ankle dorsiflexion is not available, there will be higher continuous pressure on the forefoot through the midstance and propulsive phases. Likewise, any restriction of motion at the first MPJ alters gait and elevates pressure beneath the hallux. These increased pressures due to LJM, in conjunction with peripheral neuropathy, are closely related with higher incidences of forefoot ulceration.

Over time, people with diabetes may also experience some level of muscle atrophy that deforms the toes and feet and encourages anterior migration of the plantar fat pads. These musculoskeletal changes result in midfoot bony prominences, dropped metatarsal heads, and hammertoes, which become focal sites for pressure and shear, leading to calluses on the skin. As it is established that the presence of a plantar callus is highly predictive of ulceration, inspecting for and preventing calluses is a known way to avoid ulceration.

Recommended Devices

Any AFO or mechanical intervention that limits ankle motion, keeping the foot at 90 degrees to the leg, will help reduce loading on the midfoot and forefoot later in the gait cycle. The shortened stride length and decreased cadence help reduce the intensity of repetitive cycling. As an aid to ambulation, many rigid-ankle devices are made with rockers or controlled ankle motion (CAM) soles to smooth out the step. One caution with any of these orthoses is that they may lose effectiveness if edema subsides.

Total Contact Cast (TCC)

The benchmark non-removable device and the first recommendation from the IWGDF is a knee-high TCC. The TCC ensures contact over a large surface area, which decreases peak pressure at any one location. Other benefits include blocking ankle motion, eliminating shear, reducing edema, and protecting the foot from trauma. TCCs also slow gait and reduce stride length, encouraging the patient to take fewer steps during the healing phase. The clear advantage of forced compliance also contributes to the success of the device.

Although proven to heal foot ulcers, TCCs remain underutilized. They are not the first choice for many clinicians or patients because they require practitioner experience to apply, and frequent removals and reapplications, which are costly in time and materials. To be effective, the wound must be debrided and dressed appropriately each time a fresh cast is applied. Initially the patient is seen within about three days to check on edema and the fit of the cast. After that they are scheduled every one to two weeks with the possibility that healing can occur in as little as four to five weeks. TCCs have documented healing rates of 90 percent at 12 weeks.

Contraindications for the TCC include peripheral artery disease, active infections, fluctuating leg edema, or a history of noncompliance regarding appointment protocol. TCCs may not be the best choice for patients with unsteady gait.

instant Total Contact Cast (iTCC)

Gait studies have shown that with compliant patients, removable cast walkers (RCWs) can be as effective as TCCs in reducing forefoot pressure. RCWs offer easy access to the wound for frequent assessment or application of advanced dressings if required. In addition, using off-the-shelf devices is relatively inexpensive and many come with modifiable, segmented honeycomb insoles that are very quickly and easily adjusted.

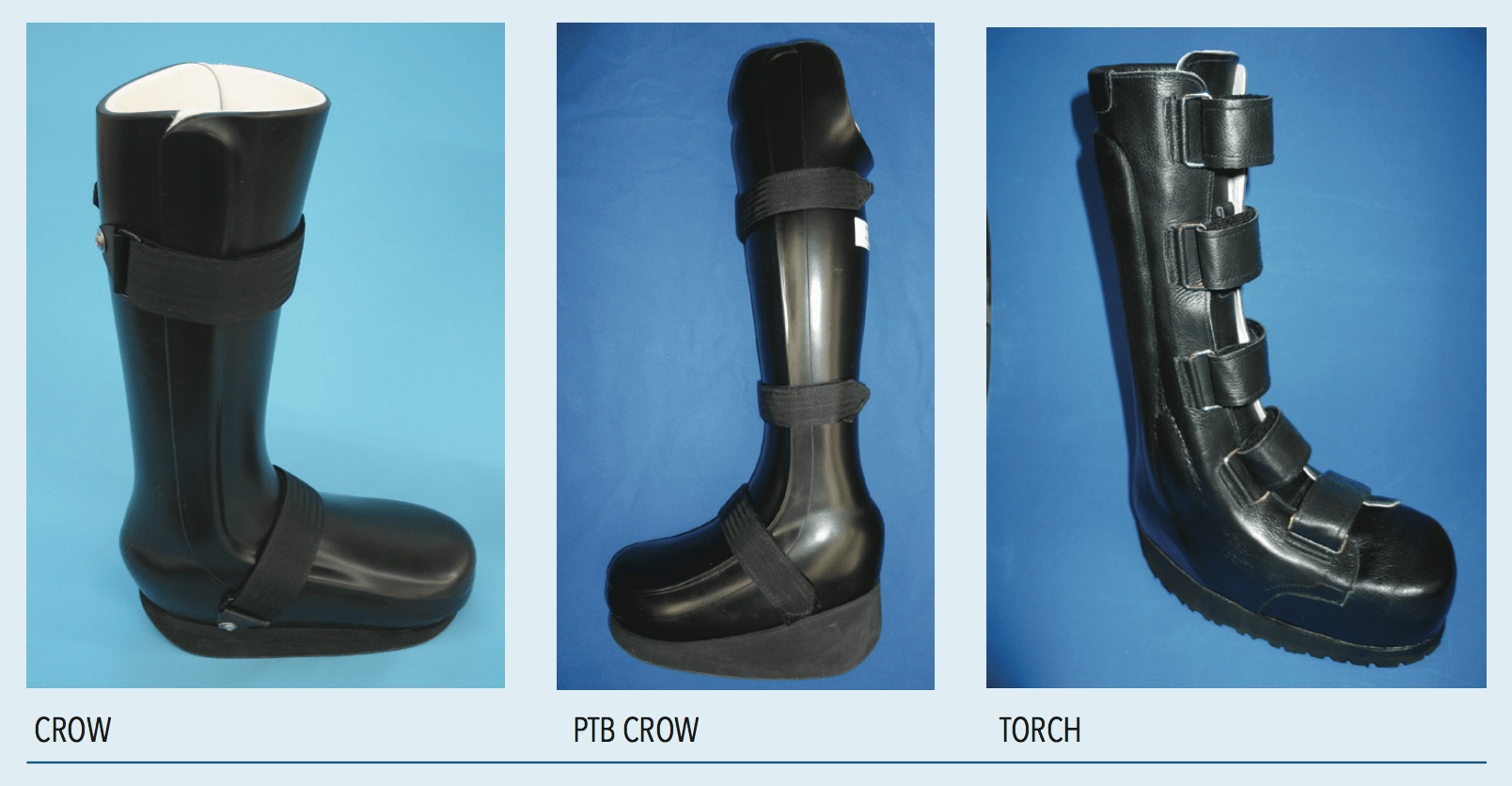

One version of an iTCC is a knee-high RCW secured by applying plastic cable ties or wrapping it with a layer of fiberglass, ensuring continuous wearing of the device. The iTCC is a way to derive the wound healing benefits of the TCC without the difficulties of multiple applications. An iTCC requires less training to administer, is easier to remove, and can be more cost effective than a TCC, yet unlike an RCW, any deviation from the treatment protocol is obvious. In cases where there is more severe deformity, a neuropathic walker such as a Charcot restraint orthopedic walker (CROW) may be dispensed and secured in the same manner.

AFOs and Ankle-high Off-loading Devices

There are many AFO designs and hybrid shoe options that enhance forefoot and midfoot wound healing. As mentioned, RCWs with a fixed ankle and rocker sole are popular and relatively inexpensive. They can be quite effective, with one study reporting ulcers healing in seven to eight weeks. Patellar-tendon-bearing orthoses (PTBs), CROWs, or suspension-style AFOs that transfer ground reaction forces away from the plantar foot are also beneficial. A total contact orthotic restraining custom hybrid (TORCH) is a combination high-trim, rigid AFO wrapped inside a custom-molded shoe. As footwear, it may have a higher probability of being worn regularly.

Although traditional AFOs and plastic-in-leather ankle gauntlets can also help healing— they restrict ankle motion— they are not nearly as effective in off-loading the plantar foot. It is also well documented that when patients can remove their devices, ulcer healing rates drop significantly.

Surgical Shoes

There are a variety of post-operative half shoes and healing sandals that can accommodate dressings and be used in the healing process. Half shoes fully unload a portion of the foot. Although surgical shoes are inexpensive and easy to administer, studies consistently show that they are not nearly as effective as rigid cast walkers that restrict ankle motion.

Felted Foam Dressing

Podiatrists sometimes use multi-layered, felted foam to off-load plantar ulcers. The felt is applied directly to the skin with a large aperture for the wound. Patients can wear a rigid-sole, post-operative shoe and have the dressing changed weekly. The main concern with cut-outs, either in felt or insoles, is the development of an “edge effect.” Care must be taken to ensure that the rim of the well or depression does not cause localized high pressure and further breakdown of the skin.

Insoles and Shoes

Later in the healing cycle, after the ulcer has been brought under control and closed, both non-custom and custom orthotics and shoes are frequently used to prevent recurrence. To be clear, the IWGDF specifically recommends not to use therapeutic footwear to promote healing of a plantar ulcer unless no other option is available.

Prevention

The IWGDF produces a separate Prevention Guideline (https://iwgdfguidelines.org/prevention-guideline) similar in scope to that of the International Diabetes Federation. First, for a person with low risk of foot ulceration they recommend an annual exam for signs of loss of protective sensation and peripheral artery disease. Patients with an established moderate risk level should be screened more frequently. All patients with diabetes who have even a moderate risk for ulceration should be urged to not walk barefoot, in socks without shoes, or in thin-soled slippers—even indoors. Formal patient education is proven to make a difference so all patients should be instructed about how to inspect and care for their feet, including daily washing, skin moisturizing, and nail care. In more severe cases, patients can be asked to self-monitor foot skin temperature daily to identify early signs of foot inflammation. (For a more complete overview, see “The Diabetic Epidemic,” March 2020, The O&P EDGE.)

Therapeutic footwear and insoles are an important part of the prevention guidelines to help avoid all-too-common recurrences. Total-contact accommodative foot molds with pockets or depressions help distribute weight evenly across the entire foot. These can be incorporated into extra- depth shoes that have special features such as sole stiffeners or rocker soles to reduce peak pressures in the propulsive phase of gait. Specialized low-friction memory foams such as Plastazote and P-Cell, and ShearBan are also used to reduce friction on the skin. Foot and mobility-related exercises that increase foot and ankle range of motion can also help reduce peak plantar pressures. Ultimately the goal is to keep the patient active, but to do so in a safe and controlled manner. Those at low or moderate risk for ulceration should be encouraged to slowly increase their level of walking, wearing appropriate footwear and monitoring foot skin integrity.

Conclusion

Chronic open foot wounds in people with diabetes need to be treated seriously due to the high cost to the patient and the community— especially if infection occurs. To avoid the possibility of amputation, off-loading is arguably the most important of multiple interventions to heal a neuropathic plantar foot ulcer in a person with diabetes. Patients frequently resist wearing rigid casts and AFOs, but their efficacy is clearly demonstrated, and it is important not to compromise the choice of device by acquiescing to a patient’s lifestyle demands. Once healed, patients should be educated and transitioned to a program of routine care and protective orthotics and shoe gear to avoid a pernicious cycle of re-ulceration.

Séamus Kennedy, BEng (Mech), CPed, is president and co-owner of Hersco Ortho Labs, New York. He can be contacted via e-mail at seamus@hersco.com or by visiting www.hersco.com.

References

- The International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot https://iwgdfguidelines.org/offloading-guideline

- McGuire, J. and Mach, S. 2017. Using the IWGDF Guidelines for Off-Loading the Diabetic Foot. Podiatry Management