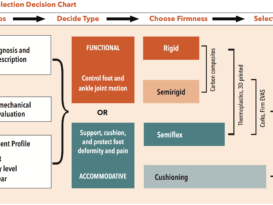

The objective of presenting pathology-specific orthotics is to describe a systematic and consistent approach to orthotic therapy. However, it is important to always consider the many factors that can influence pain or the development of an injury. Each patient is unique, and we must ask how the information gathered can be used to improve his or her life. Clinical experience, curiosity, and a thorough biomechanical examination remain foundational to achieving consistent, effective outcomes.

Low Back Pain

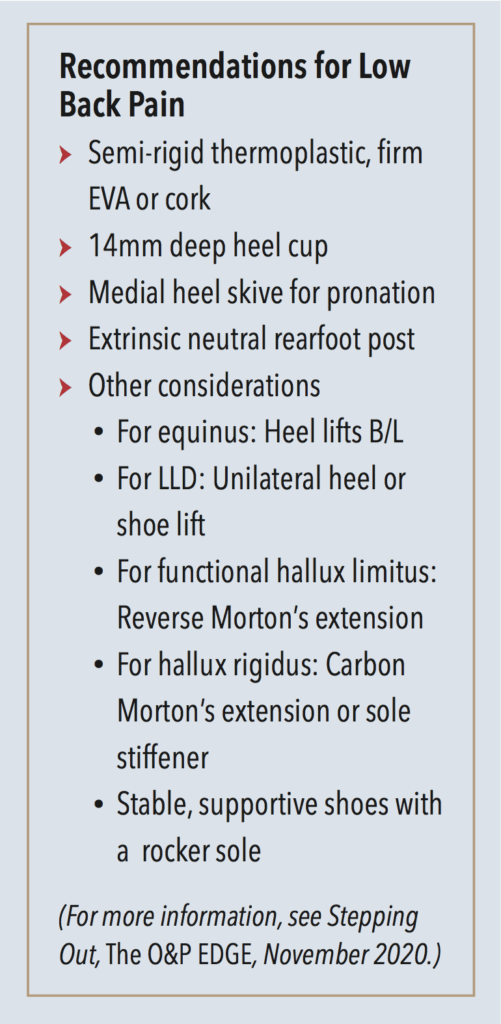

The National Institutes of Health cites many causes that contribute to low back pain (LBP). Although their list is extensive, a significant percentage of cases cannot be ascribed to a particular cause or incident but are generally associated with repetitive stress and postural statics and dynamics. Aberrations in static alignment and gait dynamics play an underappreciated role in affecting skeletal posture both in stance and gait.

It is not surprising that foot pronation has been linked to LBP. Studies show that alignment of the lower limb up to the pelvic girdle can be altered by forces acting on the foot. Pronation and foot eversion lead to internal tibial rotation and knee flexion. is in turn causes hip flexion and anterior pelvic tilt, causing spinal lordosis and compression of the lumbar vertebrae. This chain of events is easily demonstrated when patients with a flexible at foot transition between resting calcaneal stance position and neutral calcaneal stance. When they raise the arches of their feet, they automatically rotate the lower limbs outward, stand taller, and reduce lumbar curvature. Underscoring this point, in a retrospective study of almost 100,000 military recruits, moderate and severe pes planus was associated with nearly double the rate of anterior knee pain and intermittent low back pain.

Postural or gait asymmetries, leading to areas of uneven pressure or force, also play a significant role. The most obvious difference is a leg length discrepancy (LLD) where one leg is either structurally shorter or there is an imbalance in function. As the sacrum sits between the ilium supporting the lumbar spine, any imbalance distal to the pelvis can alter loads left to right and potentially be a source of LBP. Observation of any asymmetry, whether in stance, gait, foot type, or shoe wear pattern is a clue that some aspect of LLD or dysfunction may be present.

Devices designed to control and enhance motion are helpful in addressing some of the issues identified as contributing to LBP. Firstly, they counter the effects of pronation and alter posture. For patients with correctable pes planus, a semi-rigid functional orthotic with a deep heel cup will raise and maintain the longitudinal arch, limiting internal tibial rotation. Secondly, both structural and functional LLDs can be addressed using heel lifts, orthotics, and shoe lifts. Thirdly, the harmful effects of ankle equinus can be mitigated using orthotics by encouraging a symmetrical gait pattern, optimizing the timing in each step, and rebalancing ground reaction forces.

Finally, moderate restrictions in the third rocker created by functional hallux limitus can often be restored with a reverse Morton’s extension. In cases where the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) is severely arthritic and its motion is painful, it is better to dispense a rigid Morton’s extension and shoes with rocker soles.

Metatarsalgia

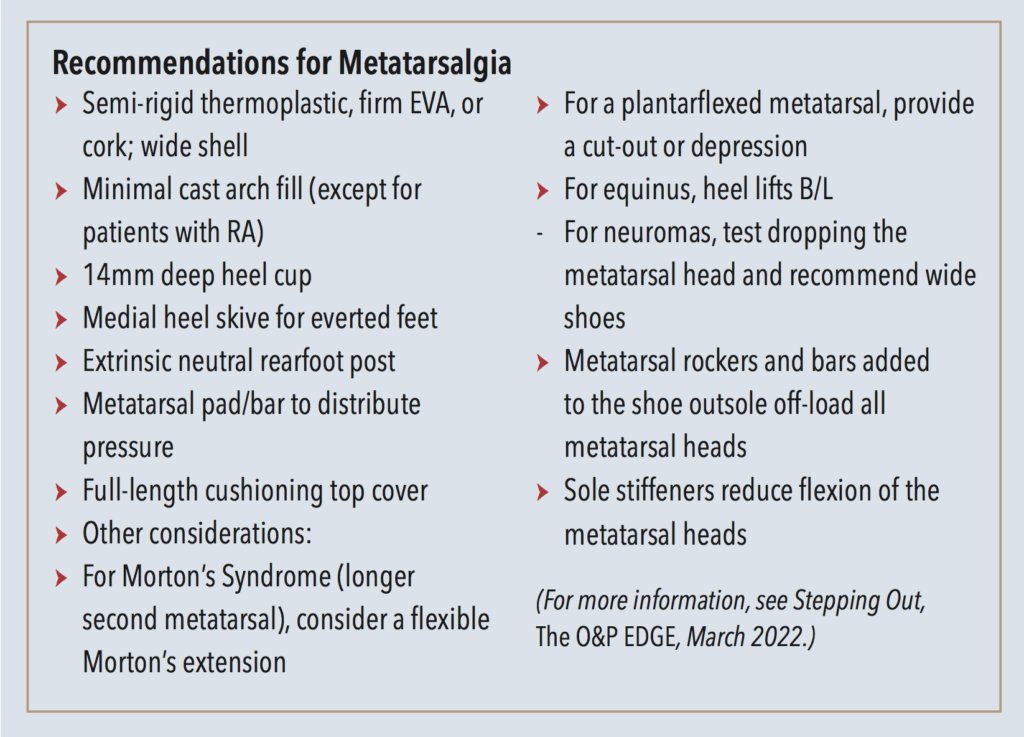

Metatarsalgia is a general term used to describe a variety of diagnoses that present as pain in the forefoot. It is considered a symptom, and it covers pain occurring at the metatarsal heads, the MPJs, or the soft tissue in that region.

Primary metatarsalgia can be structural or functional in nature—an anatomical abnormality that directly results in an imbalance causing increased pressure under the metatarsal heads. Examples include hallux valgus, hallux rigidus, a plantarflexed metatarsal bone, a hammer-toe, or pes cavus. Treatment should be focused on accommodating the uneven weight distribution at the metatarsal heads, mechanically directing force away from the point of pressure.

Secondary metatarsalgia is defined as pain with an origin beyond the metatarsal area itself. For example, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), equinus, or a LLD can lead to localized pain at the ball of the foot. Other etiologies include trauma, osteoarthritis, and neuromuscular diseases that create muscle imbalance. Effective treatment addresses the area of pain, the function of the foot and, if necessary, the systemic disease.

An appreciation of the underlying biomechanics reveals many reasons why metatarsalgia may occur. Patients exhibiting early heel rise will be at risk for developing metatarsalgia as they prematurely transfer body weight to the forefoot— loading it for a longer time. Excessive cyclical pressure can lead to keratoses, plantar plate tears, fat pad atrophy, and soft tissue inflammation. Early heel lift occurs when there is equinus or LLD. First ray function also plays an important role in gait. Hallux valgus, a short first metatarsal, or a hypermobile first ray that lacks stiffness can result in weight being transferred laterally, aggravating the lesser metatarsals. Conversely, conditions such as hallux rigidus cause too much weight to be borne by the first ray leading to pathology at the first metatarsal.

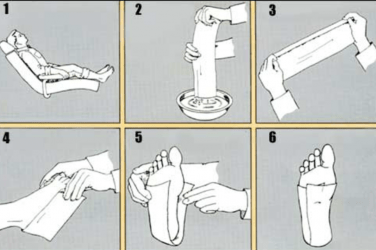

The most common approach to treating metatarsalgia is to offload the affected area through callus debridement and the application of an appropriate metatarsal pad. Metatarsal pads are made from a variety of materials and come in a range of shapes, sizes, heights, and durometers. For example, in the case of first metatarsal head pain, sesamoid or dancer’s pads are shaped to provide a deep well or relief for the head of the first metatarsal. The goal is to redistribute pressure away from the point of tenderness and shift it proximally to the shaft of the metatarsal bone or disperse the load to the lesser metatarsals.

Incorporating pads into foot orthotics offers several benefits. Firstly, the shell supports the medial longitudinal arch, distributing weight across the entire plantar foot. Orthotics act to control the dynamic foot, limiting abnormal motion. Secondly, they are transferrable across shoes, so the wearer is not restricted to certain footgear. Thirdly, the metatarsal pad size and location are fully adjustable. Specific prescription requests should include minimal plaster arch fill on the cast, a medial heel skive, and a wide orthotic shell. Where there is excessive pronation, a rearfoot varus extrinsic post will also potentially relieve symptoms in the forefoot. Finally, the addition of soft, cushioning top covers absorbs shock.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

The vast majority of patients with RA develop foot pathology, and in over one-third of cases the foot is the initial site of involvement. Rheumatologists treat RA with medication, physical therapy, orthotics, and strength and movement programs. Early intervention is essential as it can delay the onset of joint destruction and biomechanical limitations.

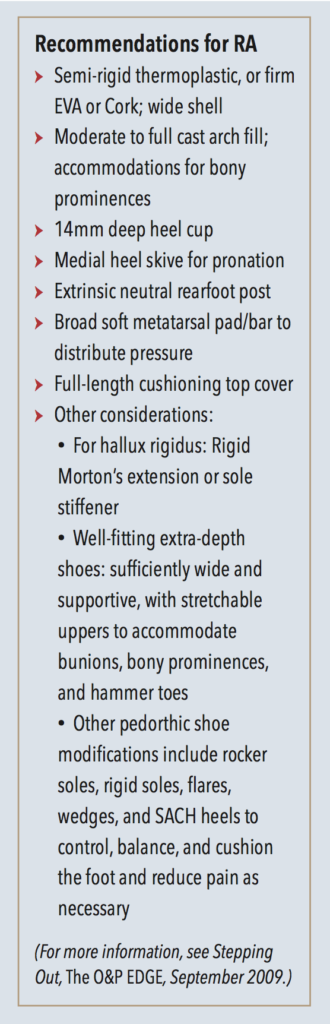

The primary aims in treating patients with RA are to reduce pain, prevent or limit further joint destruction, and keep the patient active and functioning. Typically, patients will present with combinations of metatarsalgia, rearfoot valgus, arch collapse, or first MPJ changes. Due to the painful nature of the disease and the collapsed foot structure, the conventional approach has been to prescribe accommodative orthotics that provide cushioning for the foot.

However, evidence suggests patients do quite well in functional foot orthotics. Although soft orthotics help lessen impact and relieve pressure, firm functional orthotics hold and stabilize the foot and prevent further joint destruction. There appears to be a progression in the foot pathology as follows: rearfoot valgus, arch flattening, splayfoot, and then lesser digit deformities. It is believed limiting movement away from the end range of motion better preserves the foot structures. When fabricating functional foot orthotics for RA patients, do not attempt to over correct the foot, rather build a firm plate to maintain optimum position.

Semi-rigid orthotics stabilize the rearfoot and resist excessive calcaneal valgus. Deep heel cups, intrinsic and extrinsic posting, and cast skives enhance the effect. Secondly, midfoot collapse can be controlled by requesting a wide medial trim line to capture more of the arch. A wider plate also increases the total contact surface area, redistributing pressure, but a broader foot plate only works if the patient has sufficiently wide shoes to accept the shell. If the patient has a dropped navicular, it will be necessary to accommodate that in the shell to avoid pain and irritation.

The metatarsal heads are a frequent site of pain, and good arch support can relieve some of it by transferring load proximally. Metatarsal pads, metatarsal bars, and drops can be requested as necessary. Hallux rigidus due to degradation of the first MPJ can be addressed with rigid Morton’s extensions or shoe modifications. Finally, full-length shock-absorbing top covers provide welcome cushioning.

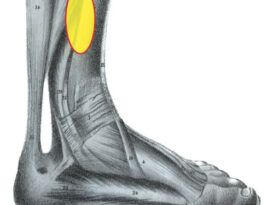

Tarsal Tunnel

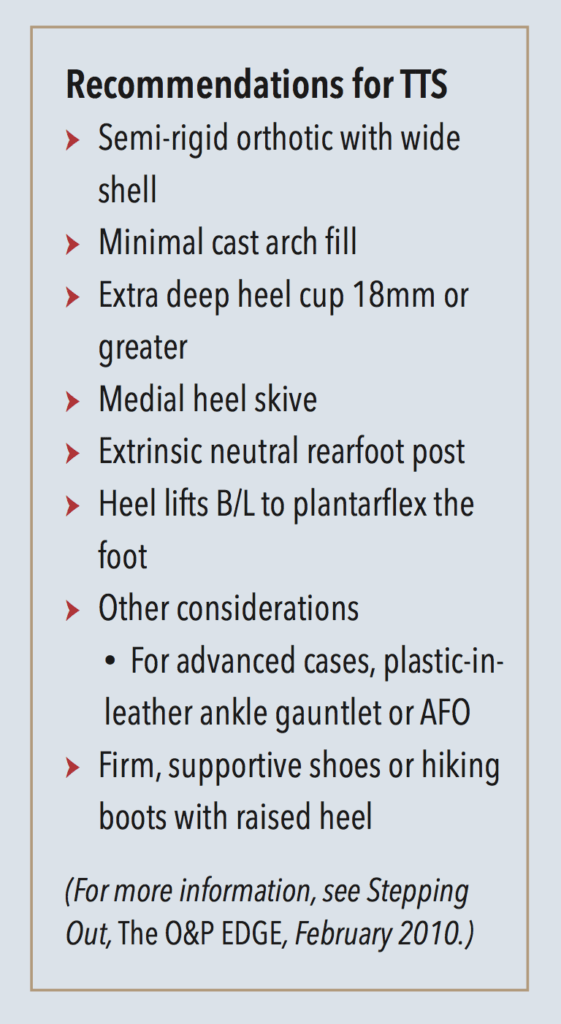

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) is recognized as pain in the proximal medial arch often accompanied by a pins-and-needles prickling sensation due to nerve entrapment or restriction. It is a painful and debilitating condition that results from compression of the posterior tibial nerve, similar to carpal tunnel syndrome seen in the wrist. The symptoms can be constant or intermittent. The tarsal tunnel is the narrow space between the flexor retinaculum and the medial talus-calcaneus. TTS occurs when there is traction on the tibial nerve and compression by the flexor retinaculum. It is frequently associated with moderate to severe pes planus indicating a strong biomechanical component. However, anything taking up space in the tunnel can increase the pressure, so TTS may also arise from swelling in the tissues, arthritis, or tumors.

TTS usually causes a vague pain in the sole of the foot and patients describe it as a burning or tingling sensation. It may occur as the result of a sprain or other traumatic injury and can be seen among athletes and active people who stress the medial ankle, making the tendon prone to swelling. Frequently the pain increases with activity and worsens as the day progresses. The symptoms may be reduced with rest, and diagnosis is confirmed using an EMG nerve conduction test. Studies show there is an increase of pressure in the tarsal tunnel compartment when the foot is pronated compared to the neutral position. It is also noted there is less pressure in the channel when the foot is slightly plantarflexed and inverted.

Foot orthotics can be used to control rearfoot motion and maintain the calcaneus in a more vertical position. Typical prescriptions include a deep heel cup and extrinsic rearfoot posting. The orthotic should be semi-rigid to provide stability and the cast modifications may include a medial heel skive to increase the ground reaction force. Finally, heel lifts of five millimeters or more slightly plantarflex the foot, reducing pressure in the tarsal tunnel. Well-fitting, supportive shoes are also important as firm high counters buttress the orthotic, resisting the tendency of the ankle to collapse. External shoe modifications such as a medial flare may also provide some benefit. In more advanced cases,

a plastic-in-leather ankle gauntlet or other AFO may be prescribed to restrict subtalar joint and rearfoot motion, alleviating the pain.

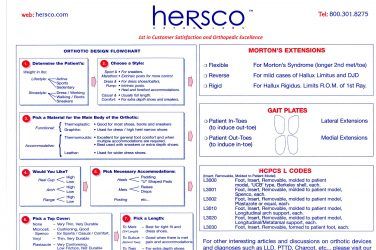

It is important to remember, for any diagnosis there can never be a single design that will work for everyone as there is too much variation in human anatomy and patient lifestyle. Further complicating the issue, multiple factors often contribute to a diagnosis and similarly, a dysfunction may lead to several distinct pathologies. These helpful algorithms have been established as an initial guide in the design and decision-making process.

Séamus Kennedy, BEng (Mech), CPed, is president and co-owner of Hersco Ortho Labs, New York. He can be contacted via e-mail at seamus@hersco.com or by visiting www.hersco.com.